Branding: Coordinating My Wardrobe to the HARP Colour Palette

Posted by Dorothy Lander: dorothy@tryhealingarts.ca The talented team at This is Marketing (https://www.thisismarketing.ca/) chose a unique colour palette to illuminate

John and I have taken to reading aloud Nature writing first thing in the morning. Yesterday, we were so sad when we came to the end of Dara McAnulty’s Diary of a Young Naturalist—we did not want the poetic beauty to end. John has been observing and remembering the times when he has cried, even sobbed. He was an adult before he could cry about the loss of his beloved mother, who died when he was just aged 12, a schoolboy at Epsom College in England. Yet he is often moved to tears by beauty, which can take the form of acts of courage or Nature’s beauty. He was moved to tears by both instances of beauty in Dara’s writing, in which he interweaves his ways of being an activist for our climate emergency with his experiences of being autistic and finding solace and joy from being in Nature. Inseparable ways of being.

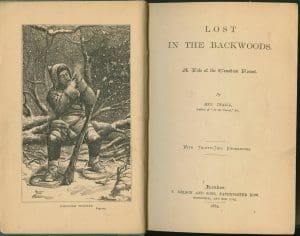

Today (Oct 18, 2020) for our reading aloud, we picked up a significant book from Dorothy’s childhood—Lost in the Backwoods: A Tale of the Canadian Forest—a children’s story written by botanist Catharine Parr Traill (CPT) in 1850 and reissued in 1923 as Canadian Crusoes: A Tale of the Rice Lake Plains. Dorothy was moved to tears as she began to read Chapter 1.

“The morning had shot her bright streamers on high,

O’er Canada, opening all pale to the sky:

Still dazzling and white was the robe that she wore,

Except where the ocean wave lash’d on the shore.”

– Jacobite Song

There lies between the Rice Lake and the Ontario a deep and fertile valley, surrounded by lofty wood-crowned hills, the heights of which were clothed chiefly with groves of oak and pine, though the side of the hills and the alluvial bottoms gave a variety of noble timber trees of various kinds, the maple, beech, hemlock, and others.

Mrs. Traill’s children’s story has had Dorothy’s attention recently on two accounts.

Dorothy also adopts Mrs. Traill’s practice of giving the classification name for the plants that feature in her story. Here is how CPT describes the Valley of the Big Stone:

“Morning glory,” (Convolvulus major) and scarlet-cups (Euchroma, or painted-cup) in abundance, with roses in profusion. The bottom of this ravine was strewed in places with huge blocks of black granite, cushioned with thick green moss; it opened out into a wide flat, similar to the one at the mouth of the valley of the Big Stone.

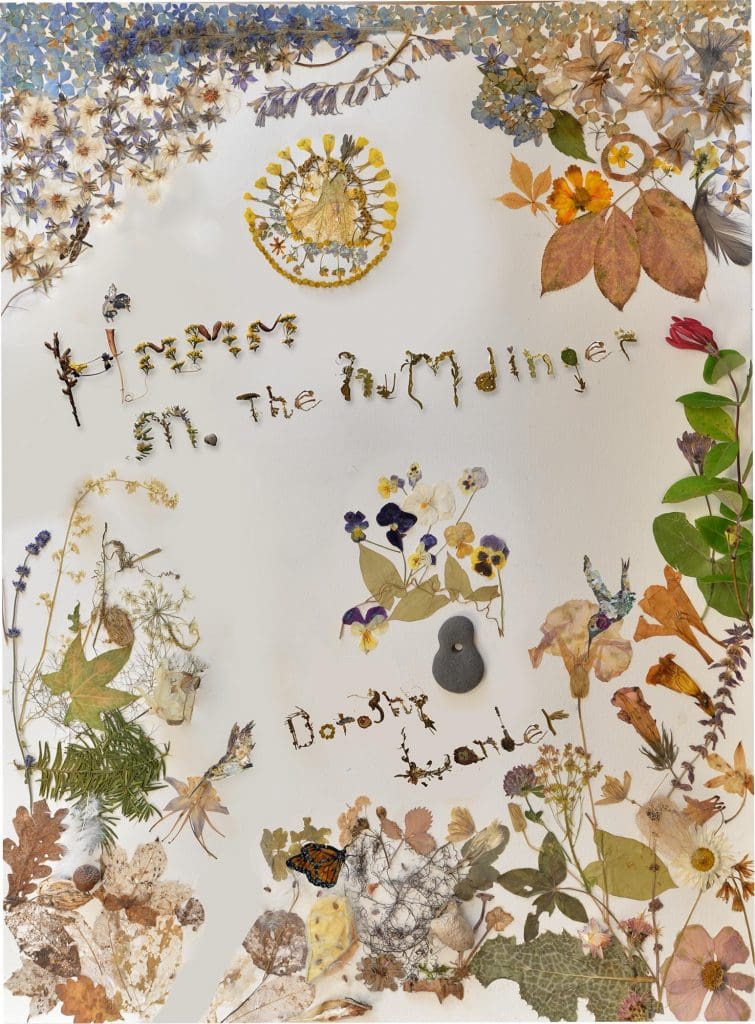

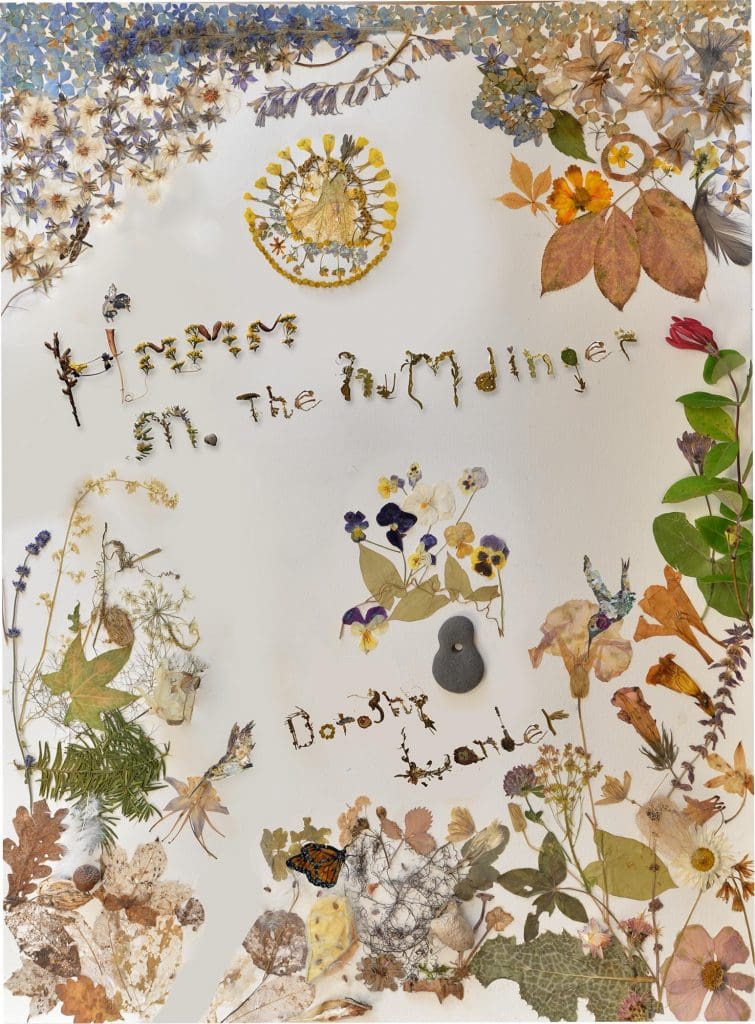

Most of the pressed and dried botanicals that make up the collages and the companion hummers in Hmmm—hummingbirds, bees, dragonflies, butterflies—come from within a 20-mile radius of where we now live in northeastern Nova Scotia, but the miniature white roses (rosa blanca) are descendants of the white roses from the Valley of the Big Stone on the Lander family farm.

And then, Mrs. Traill’s prophetic footnote leads to our second topical reason for reading her children’s story aloud:

The mouth of this ravine is now under the plough and waving fields of golden grain and verdant pastures have taken place of the wild shrubs and flowers that formerly adorned it.

Reading Lost in the Backwoods reminds us, that as David Suzuki insists, Indigenous People, not environmentalists, are our best bet for protecting the planet.

Dorothy’s memory of reading this book and/or having this children’s story read to her, was that it celebrates the friendship between settler children of Canada’s French and English Nations and the Mohawk child whose knowledge of the woods ensured their survival. This reading stands as a symbol of frontier history in which Indigenous knowledge of the ways of the land was the source of survival and continues to be in the face of our present climate emergency. CPT in the mid 19th century was decrying “the forest is disappearing, the white man is everywhere.”

Dorothy’s memory of friendship and reconciliation in Lost in the Backwoods was also sparked by the violence perpetrated on Mikmaw fishers by commercial fishers in Mi’kma’ki. A large fire completely destroyed a lobster pound being used by Mi’kmaw fishers in Middle West Pubnico, Nova Scotia, on early Saturday morning (Oct. 17). The blaze comes just days after police confirmed two raids took place on lobster pounds by commercial fishers protesting a “moderate livelihood’ fishery launched by Sipekne’katik First Nation last month. Sadly, Mrs. Traill’s 1850 children’s story reinforced the “noble savage” discourse and played out their menacing roles of frontier fiction alongside the superiority of the religion and education of the “white man.” These residual attitudes spawn violent acts and systemic racism that has been playing out in Mi’kma’ki.

Even as we are drawn to Mrs. Traill’s beautiful Nature writing, we know we must read through a discerning and critical lens acknowledging the racist attitudes that have been instilled in our consciousness from our first experiences of reading.

Posted by Dorothy Lander: dorothy@tryhealingarts.ca The talented team at This is Marketing (https://www.thisismarketing.ca/) chose a unique colour palette to illuminate

L to R Clockwise: John Graham-Pole aged 2 on Mummy’s knee with sisters Elizabeth, Mary, and Jane, High Bickington, Devon,

Posted by Dorothy Lander Once a month, John Graham-Pole and I showcase the publications of HARP The People’s Press at

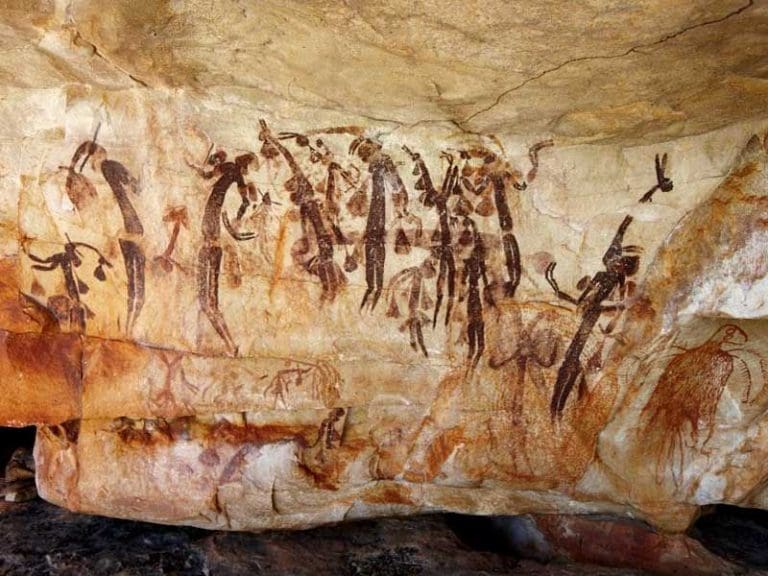

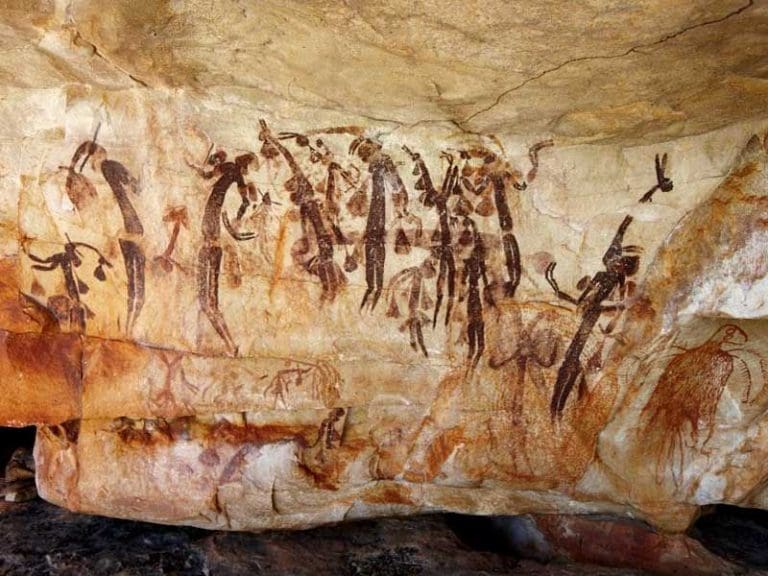

Aboriginal Rock Mural Kimberley Region, Western Australia Posted by John Graham-Pole I don’t have answers to any of these questions,

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |