Branding: Coordinating My Wardrobe to the HARP Colour Palette

Posted by Dorothy Lander: dorothy@tryhealingarts.ca The talented team at This is Marketing (https://www.thisismarketing.ca/) chose a unique colour palette to illuminate

METAMORPHOSES

Plant-Patty and Miss Birch Turn into Each Other

Let me sing to you now, about how people turn into other things.

In the fall of 2020, John Graham-Pole and I embarked on a pandemic reading program. Reading that would keep us attuned to the global climate emergency. We began to read aloud to each other from Nature books before we got up in the morning.

Our first reading was Canadian Crusoes, penned by Catharine Parr Traill in 1852, the first Canadian work of children’s fiction. The novel includes descriptions of the Indigenous practice of burning grass on the hills surrounding Rice Lake as a way to create abundant food for deer. These are the burns now prescribed by the Nature Conservancy of Canada, which has identified the Rice Lake prairie and savannah as one of the world’s rarest and most endangered ecosystems. Over the past year, we read aloud Diary of a Young Naturalist by Dara McAnulty, The Life of the Bee by Maurice Maeterlinck, Braiding Sweetgrass by Robin Wall Kimmerer, The Wild Remedy by Emma Mitchell, and Dancing with Bees by Brigit Strawbridge Howard.

By the fall of 2021, we were reading Richard Powers’ 2018 novel The Overstory and Suzanne Simard’s 2021 research memoir Finding the Mother Tree, on alternate days. Both John and I proudly call on our Classics education; we both studied Latin for several years, John in public school in England, and Dorothy at high school and university in Ontario. We were thrilled when we came to the passage in Powers’ chapter “Patricia Westerford” where she reads the first sentence from from her father’s gift to her of Ovid’s Metamorphoses.

Let me sing to you now, about how people turn into other things.

Patricia loves the stories of people changing into trees: Daphne turned into a bay laurel; the women killers of Orpheus whose toes run into roots and their legs into woody trunks; the boy Cyparissus whom Apollo converts into a cypress; the gods change the pregnant Smyra (Myrrha) into a myrtle tree; Baucus and Philemon spend a lifetime together as oak and linden. Reading this I was over the moon; in the fall of 2020, my children’s story of a child turning into a honeysuckle bush—Hmmm – M the Humdinger—was released by HARP Publishing The People’s Press. (www.harppublishing.ca/books/hmmm). I describe my humming heroine “M” as a child of nature, who communicates entirely by humming. The illustration of “M” becoming a Honeysuckle is crafted from pressed botanicals, gathered from my garden and the wilds of Nova Scotia.

We continued to read voraciously from Simard and Powers. As Patricia grows up, her body metamorphoses; she is “clumsy and green” in her first sexual encounter. When Patricia enters university, her calling to spend her life studying all things botanical earns her the name of Plant-Patty. When Suzanne Simard presents her research that challenges the wholesale removal of birch trees in fir plantations, Forester Rick needles her, “Well, Miss Birch… You think you’re an expert…. You have no idea how these forests work” (p. 206).

It is when Plant-Patty enters graduate school—Forestry school—and spends long days in the Indiana woods doing her research, that John and I do a double take. Which book are we reading? Patricia Westerford is troubled that the “men in charge of American forestry” are speaking of thrifty young forests and decadent old ones, of mean annual increment and economic maturity. (pp 124). Patricia is sure that “trees are social creatures…[and] must have evolved to synchronize with one another. Finding out becomes the research priority for her dissertation when she gets hold of an early prototype quadruple gas chromatography-mass spectrometer. Plant-Patty becomes Dr. Pat Westerford to disguise her gender in professional correspondence.

But didn’t we just read this story a week ago? Suzanne Simard is troubled with the government’s free to grow policy to get rid of neighboring plants, including native plants so that conifer seedlings could grow without competition (p. 84).

At Forestry school, Plant-Patty is dismayed that the professor advocates for cleaning up the forest floor and pulping it to improve forest health. Surely a healthy forest must need dead trees (p. 121). Meanwhile, Suzie Simard is in charge of an experiment to test how effectively different volumes of herbicides (Monsanto) would kill native plants and “release” the understory seedlings from competition (p 86). The remaining planted prickly spruce seedings could have all the light, water and nutrients. Suzie Simard is in tears—“these plants were my allies, not my enemies” (p. 90).

Plant-Patty’s work isn’t glamorous. She tapes numbered plastic bags over the ends of branches, then collects them at measured intervals. “she does this over and over, dumbly and mutely, hour by hour” (p. 125). Suzie Simard’s experiment meant painting every one of 81,600 planting spots on the ground (p. 97). We would inject the bag over the birch with carbon dioxide tagged with the carbon-14 isotope, and we would inject the bag over the fir with carbon-13-tagged carbon dioxide, which they’d absorb over a couple of hours through photosynthesis (p. 151).

Plant-Patty works all day in the woods, her back crawling with chiggers, her scalp with ticks, her mouth filled with leaf duff, her eyes with pollen, cobwebs like scarves around her face, bracelets of poison ivy, her knees gouged by cinders, her nose lined with spores, the backs of her thighs bitten Braille by wasps, and her heart as happy as the day is generous (p. 125).

Suzie Simard sets up a tent at the site chosen to track radioactive carbon-14 travelling between tree species, because the mosquitoes were as big as snipes.…Each breath brought in a fluttering insect. … In the time it took for me to race to the truck to grab the syringes and gas tanks and run back to the tent and zip up the door, my face was raw with bites (pp. 150-151).

The press picks up on Plant-Patty’s findings and runs with the headline “Trees Talk to One Another.” Leading dendrologists say her methods are flawed and her statistics problematic (p. 126). Meanwhile, one of the head policymakers in the Forest Service scowled after Suzie’s well-prepared slide presentation. The Reverend and vegetation management forester Joe snickered to each other. The policymakers were muttering and demanding longer-term data, explaining that plantations would become brush field if “weeds” like birch were left unchecked (p. 135). Suzie Simard’s research on the flow of nutrients from tree to tree, from species to species is published in Nature; they call her discovery the wood-wide web. The article receives international press but does not budge the Forest Service policies (p. 165). The complaints about her journal article flow in dismissing her methodology and her interpretations of findings (p. 173).

The co-incidences of Plant-Patty and Suzie Simard morphing into each other kept piling up. Was this Life imitating Art? Was this universal mind at play – Rupert Sheldrake’s morphic resonance? We googled and found a 2021 article in Scientific American that revealed that indeed Suzanne Simard, the University of British Columbia ecologist was the model for Patricia Westerford in Richard Powers’ 2019 Pulitzer Prize–winning novel The Overstory.

But Richard Powers’ The Overstory was released three years before Suzanne Simard’s Finding the Mother Tree. How could Powers have gleaned the extraordinary resonance in the details right down to the size of the mosquitoes from reading Simard’s research papers or talking to her? As researchers ourselves, we cannot commit to the level of meticulous data gathering and recording that Plant-Patty and Suzie Simard excel at. But we are now on full alert to gather data to support the phenomenon that readers can and do perform like human mycorrhizal fungi to transmit our flights of imagination from writer to writer, from reader to reader, from writer to reader, from reader to writer.

For their next read-aloud, John and Dorothy have committed to read Ovid’s Metamorphoses in its original Latin, beginning with the first four famous lines.

In nova fert animus mutatas dicere formas

corpora; di, coeptis (nam vos mutastis et illa)

adspirate meis primaque ab origine mundi

ad mea perpetuum deducite tempora carmen.

(Met. 1.1–4)

My mind compels me to sing of shapes changed into new bodies:

gods, on my endeavours (for you have changed them too)

breathe your inspiration, and from the very beginning of the world

to my own times bring down this continuous song.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Constanta_-_Ovid-Platz_-_Statue_des_Ovid.jpg

Schiffman, Richard. “Mother Trees” are Intelligent: They Learn and Remember, Scientific American, May 4, 2021. Accessed Oct. 26, 2021. https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/mother-trees-are-intelligent-they-learn-and-remember/

Posted by Dorothy Lander: dorothy@tryhealingarts.ca The talented team at This is Marketing (https://www.thisismarketing.ca/) chose a unique colour palette to illuminate

L to R Clockwise: John Graham-Pole aged 2 on Mummy’s knee with sisters Elizabeth, Mary, and Jane, High Bickington, Devon,

Posted by Dorothy Lander Once a month, John Graham-Pole and I showcase the publications of HARP The People’s Press at

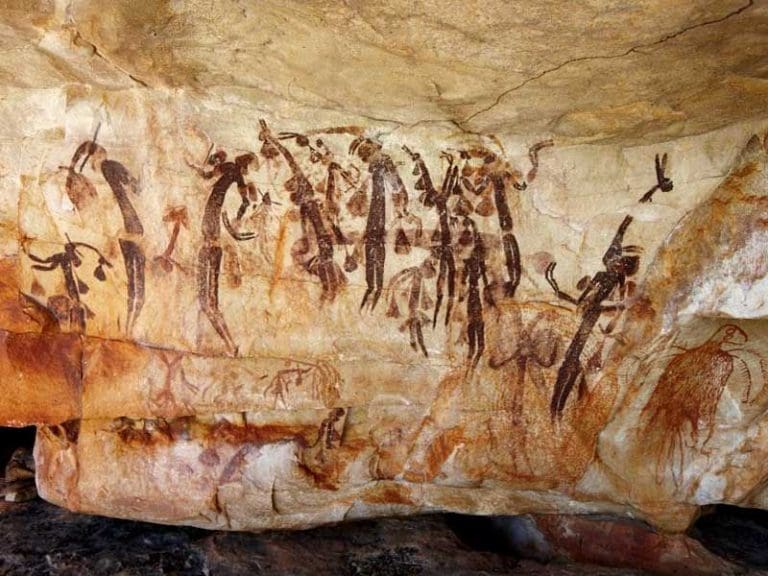

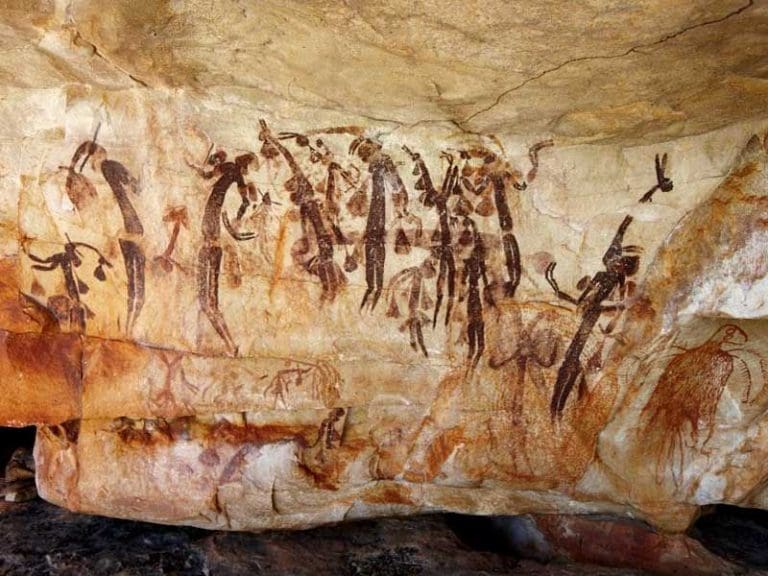

Aboriginal Rock Mural Kimberley Region, Western Australia Posted by John Graham-Pole I don’t have answers to any of these questions,

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |