Branding: Coordinating My Wardrobe to the HARP Colour Palette

Posted by Dorothy Lander: dorothy@tryhealingarts.ca The talented team at This is Marketing (https://www.thisismarketing.ca/) chose a unique colour palette to illuminate

Travels with a Low-Carbon Couple

In the summer of 2019, John and I stopped mowing the field around our solar tracker, to allow the whole space to develop into a bee and butterfly garden. More dandelions than grass, anyway, so it did not qualify as lawn by most standards. In no time, dandelions (taraxacum officinale), ox-eye daisies (chrysanthemum leucanthemum), self-heal (prunella vulgaris), Queen Anne’s Lace (daucus carota), buttercups (ranunculus acris), and several varieties of clover took over, especially red clover (trifolium pretense). This fast-growing activity in the plant world in turn created a great buzz among the creature pollinators.

Popular culture is taking up the theme. An article in The Guardian (Feb. 1, 2020) urges gardeners not to mow their lawns to help the bees. Minnesota will pay homeowners to replace lawns with bee-friendly wildflowers, clover and native grasses.

Around 55 of Minnesota’s 350 bee species depend on white clover alone. “So just by not treating white clover like a weed and letting it grow in a yard provides a really powerful resource for nearly 20% of the bee species in the state,”

“I know where the beez have gone” by the band Slambovian Circus of Dreams, leads off:

I’ve stopped cutting grass

I stopped trying to control the world.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lfA6Lhv8fAc

We both read one of Dorothy’s childhood favourites, The Keeper of the Bees, a 1924 novel by American naturalist Gene Stratton-Porter. As a primer for gardeners and beekeepers who aim to attract pollinators of all kinds, it rings true a century later. The first question the keeper of the bees had for ‘little Scout’ was; “Why is the bee garden blue?” The answer:

“Because of God. … because blue is the ‘perfect color’ and bees are the most perfect of any insect in the way they live, and the most valuable on account of the work they do. … And because why—the nearest we come to a perfect insect loves a perfect color best, why, that’s because God made them as they are!” (p. 135)

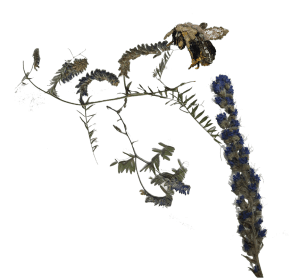

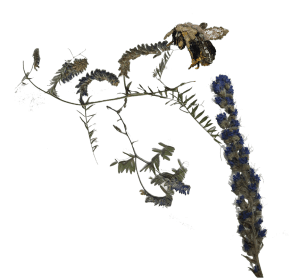

And Dorothy has filled these winter days by throwing her creative energies into an art form that she first explored as a very young child—that of pressing leaves and flowers. From a myriad of these pressed botanicals, she has created a bumble bee with wings of skeletonized leaves, and laden with pollen made of St. John’s Wort (hypericum frondosum), greater quaking grass (briza maxima), and bunny tails (lagurus ovatus). Well named bombus impatiens, s/he is in blue heaven, feasting on nectar from purple crown vetch (coronilla varia) and viper’s bugloss (echium vulgare). The blue-mauve-purple spectrum is already well represented in our regular garden — with lupins (lupinus perennis), borage (borage officianlis), hyssop (hyssopus officinalis), hydrangea (hydrangea macrophylla), lavender (lavendula angustifolia), and blue false indigo (baptisia australis). And we hold out hope that some of the self-seeders will escape to the bee and butterfly garden.

At the end of last summer, Dorothy scattered milkweed seed pods all around our new bee and butterfly garden, and also planted a mound of wild asters, both purple (radula) and white (umbellatus). The monarch butterfly (danaus plexippus) feeds almost exclusively on milkweed, and we have a healthy constellation of orange (asclepias tuberosa), white, and pink in our garden. It self-propagates every year. In 2019, to our alarm, only one monarch visited the garden and stayed for only one day. Dorothy followed her path from the pink to the white milkweed (asclepias incarnata) in two different gardens. Meanwhile, the red admirals (vanessa atalanta), not so discriminating were frequent visitors to many of our blooming plants, including milkweed.

The common milkweed (asclepias syriaca) is actually not all that common in northern Nova Scotia, but Dorothy spotted some seed pods at the Moncton VIA rail station when we stopped there on our return train trip from Saskatoon in September.

The Planted Well research site – “12 Best Flowers for Bees” – affirms that we have chosen well in the first year of our bee and butterfly garden.

Dorothy was prompted to add to this blog this week in the wake of increasing media attention to the urgency of protecting our pollinators and all insects, and also ensuring the safety of our activists and defenders of insect habitats. The article in The Guardian revealed that “the global mass of insects is falling by 2.5% a year and many could be extinct within a century, according to a global scientific review last year.”

We in Canada need to care about the overwintering of the Monarch Butterfly. Millions of these orange and black insects make a 2,000-mile (3,220-km) journey each year from Canada to winter in central Mexico’s warmer weather.

And in the past week, two defenders of the overwintering habitat of the monarch butterflies in Mexico were found dead in the state of Michocan. This is also the site of illegal logging and rival drug gangs who battle to control smuggling routes through often-arid terrain to the Pacific and the interior of the country. Conservationist Homero Gómez González was found dead on Jan. 29, 2020, near the butterfly sanctuary. He may have been targeted because of his activism by those involved in the local illegal logging industry. The 50-year-old butterfly defender’s family had already told the media that he had received threats from a criminal organization.

Tour guide Raul Hernandez, who also worked at the butterfly reserve, was found brutally murdered just two days after the former environmental activist was buried. As a memorial to these two guardians of the Monarch, Dorothy collaged a monarch from nasturtium petals and Queen Anne’s Lace and posted it on social media.

Shown here with asclepias tuberosa in bloom and the seed pods of the common milkweed (asclepias syriaca).

Posted by Dorothy Lander: dorothy@tryhealingarts.ca The talented team at This is Marketing (https://www.thisismarketing.ca/) chose a unique colour palette to illuminate

L to R Clockwise: John Graham-Pole aged 2 on Mummy’s knee with sisters Elizabeth, Mary, and Jane, High Bickington, Devon,

Posted by Dorothy Lander Once a month, John Graham-Pole and I showcase the publications of HARP The People’s Press at

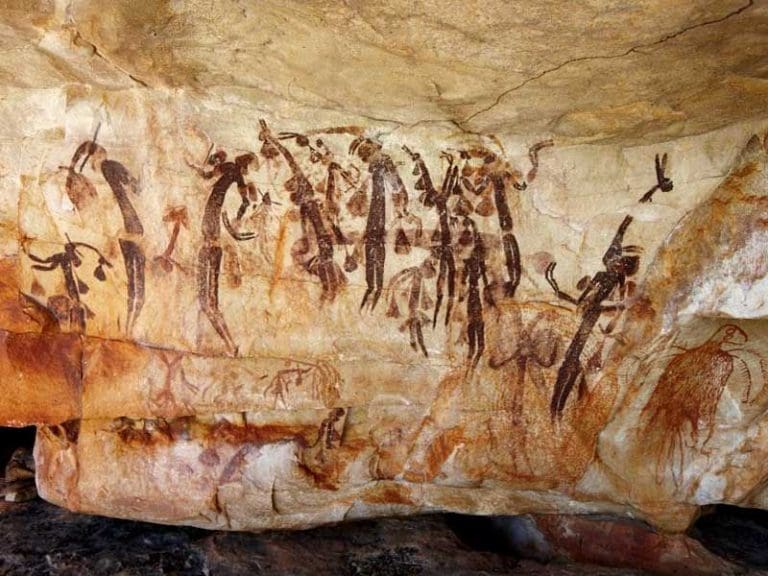

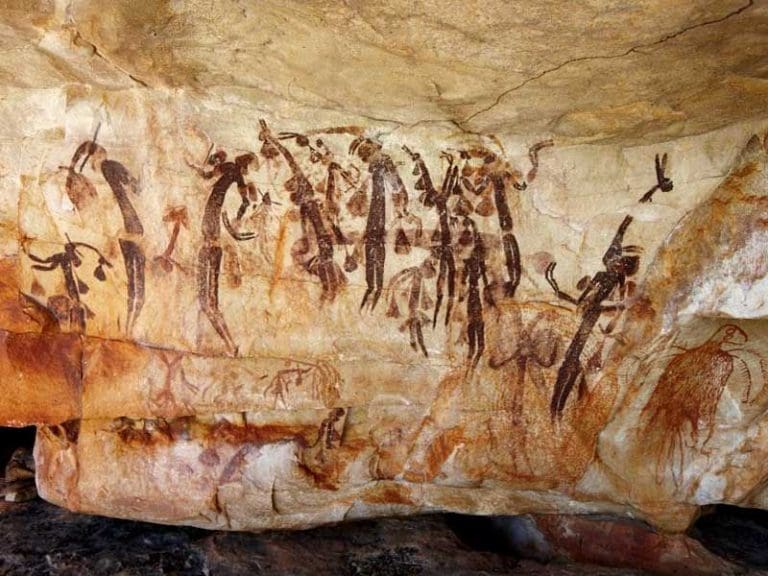

Aboriginal Rock Mural Kimberley Region, Western Australia Posted by John Graham-Pole I don’t have answers to any of these questions,

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |