Branding: Coordinating My Wardrobe to the HARP Colour Palette

Posted by Dorothy Lander: dorothy@tryhealingarts.ca The talented team at This is Marketing (https://www.thisismarketing.ca/) chose a unique colour palette to illuminate

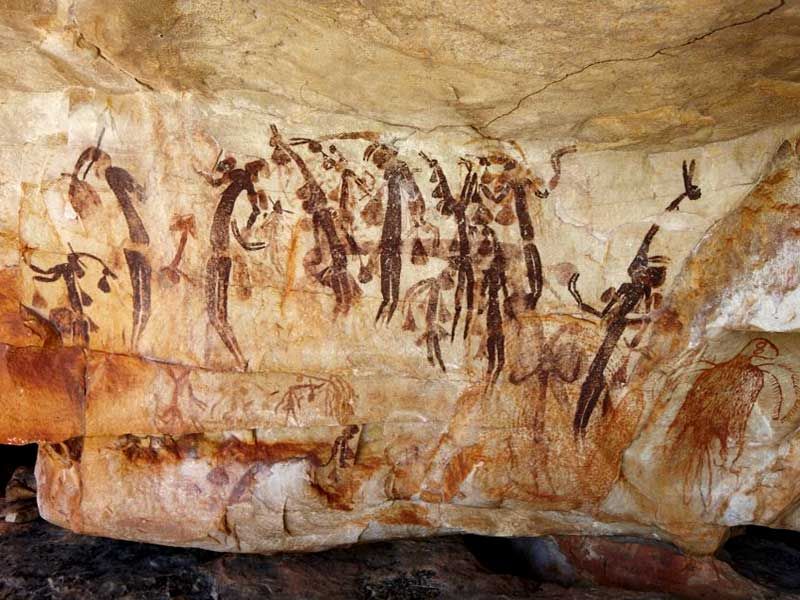

Aboriginal Rock Mural Kimberley Region, Western Australia

Posted by John Graham-Pole

I don’t have answers to any of these questions, but I can tell you a story. It’s 1960, and I’m entering St. Bartholomew’s Hospital Medical School in the city of London on a quite unlooked for scholarship in Classical languages. It’s true I’ve been totally immersed in Latin and Greek and Ancient languages for the last three years but my flimsy resume discloses not the flimsiest sliver of science. But isn’t studying medicine all about chemistry and physics and biology, topics I’ve managed to so successfully avoid in my entire education to date? I settle into the back row for my first-ever Physics lecture and greet several new colleagues. And swiftly find out we’re all in the same boat: arts and humanities scholars to a person; not an atomic particle amongst us.

A memory nudges me: a year ago I’d been lucky enough to hear the molecular physicist CP Snow give the annual Rede lecture at Cambridge University. It was its intriguing title—“The Two Cultures”— that had caught my attention: It turns out that Lord Snow blames every worldly woe on the modern schism between the sciences and the arts. So that must be what’s going on: Barts Medical School has summoned us humanists to the rescue: they’re placing the entire reunification of science and art upon our unsuspecting shoulders.

But this glorious challenge proves an evanescent dream. We historians, linguists and artists sink beneath the waves of science and technology engulfing us over six arduous years, with no relent. We never again hear that elegant word, Humanities, uttered in these halls of academe. My poetic heart bows beneath a head choc-a-block with this stuff. One solace only endures: I uncover in the turgid pages of Gray’s Anatomy those beloved words that had begun to fade from memory, each one instantly recognizable, instantly translatable: phalangeal, dorsiflexion, umbilical, epithelium, synovia, orbicular, encephalon….

The time comes for me to lay callow hands upon a patient’s naked form. What should be revered in its intimacy quickly becomes a detached diagnostic act. Before my first physical examination, the medical intern commands me:

“Never forget! Shake hands with your patient!”

I make my way towards the ancient lady assigned to my care, rubbing surreptitious hands together to warm them. And am instantly transfixed by the skeletal ballet playing out before me: radial hump and metacarpal ribs pronating and supinating beneath translucent skin. Familiar images leap instantly from the greasy pages of my dog-eared Cunningham ‘s Textbook: unnamed cadavers I’ve so recently dissected: fragile beauty transformed into a living document.

Forward fourteen years to my doctoral defense: a half-decade of painstaking research on experimental therapies for cancer. After wading through the tome before him describing in excruciating detail how I’d infused white blood cell concentrates into children with devastating infections from the impact of our chemotherapy, the committee chair announces: “We accept the results of your research, doctor.” Then pauses. “Bar one… ah, discrepancy. So, we will award you your dissertation on condition that you remove page 160 of all five copies before us.”

He hands me a pair of scissors and watches closely as I reduce each bound volume from 276 to 275 pages. My heady ten-year passion with medical science is instantly squelched: there has to be more to it than this reductionism that’s dominated medicine for two-hundred years. Half my wits may have been obsessed for the past decade and a half with statistical data—but has the other half of my brain been totally asleep? What can science and technology tell me about creativity, about imagination, about consciousness?

The well-learned analytic acumen in my hands gives way to something utterly new: the touch that evokes healing. It takes a 21-year-old patient—Janet, I call her—to point the way: how I can unite art with science. Janet’s just been awarded a full scholarship to the University of Chicago—the country’s most costly university—and is embarking on her master’s degree in fine arts when she develops cancer in her left femur and both lungs. Her family consults me at the University of Florida where I’m directing bone marrow transplantation.

“Can stem cells cure our daughter?”

“I believe it’s the best chance she has—but it’ll be a rough ride. Stem cell transplants are the most intensive cancer treatment we have.”

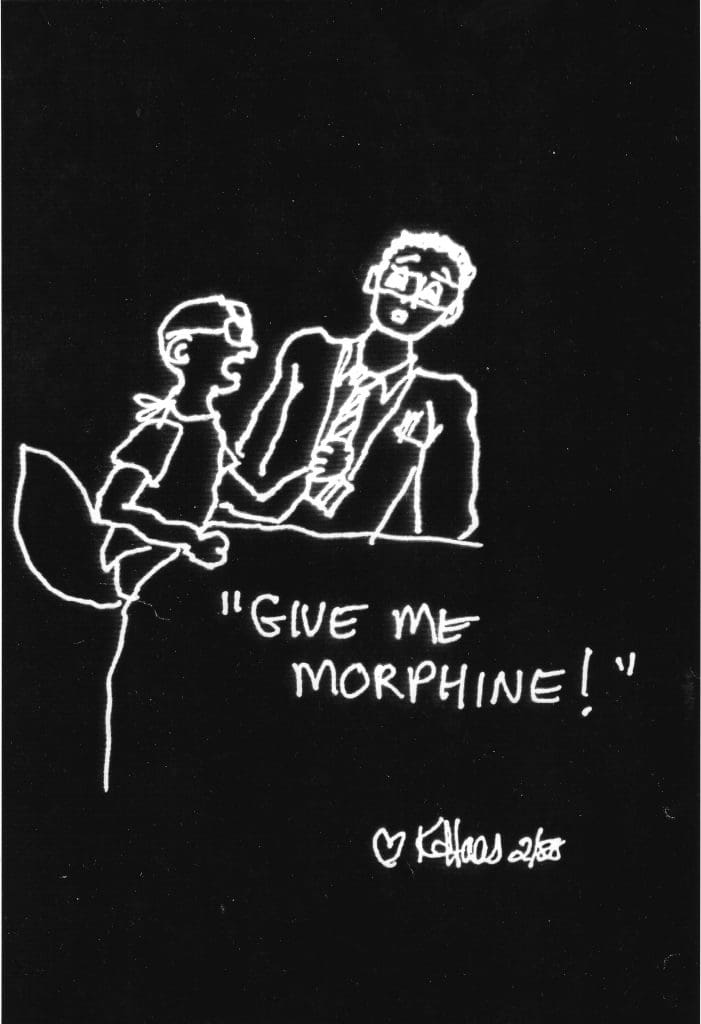

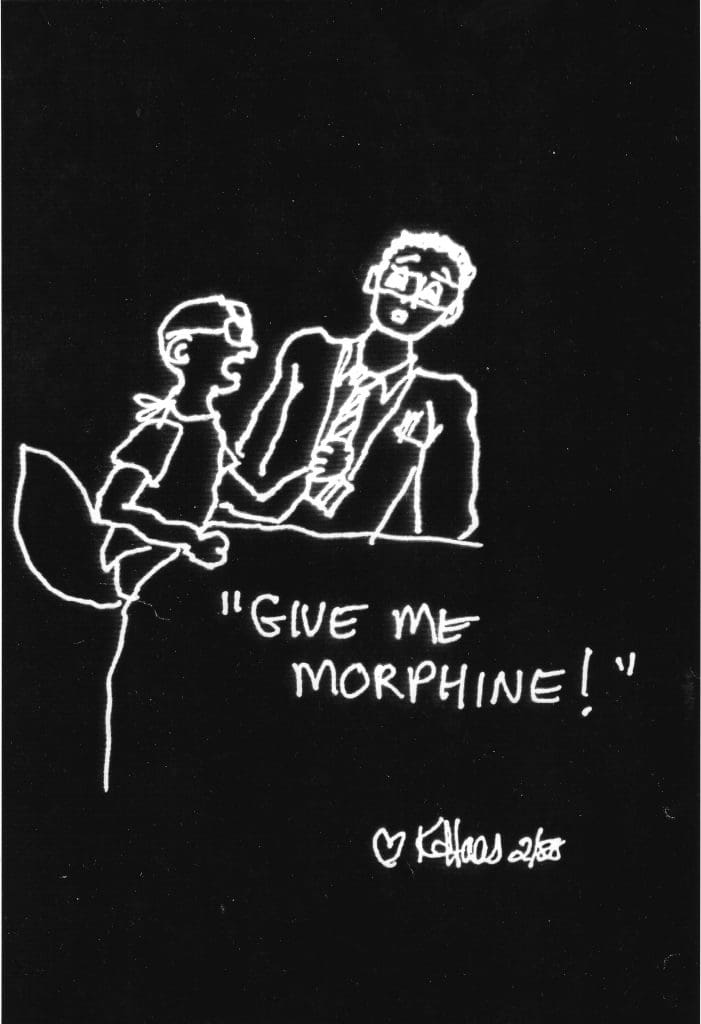

A week later I’m approaching Janet’s bedside on morning rounds as our horrific treatment effects—total sloughing of the lining of her oral and pharyngeal mucosa—are reaching their peak. I open my mouth to say good morning; she grasps my tie, and my full attention.

“Give me morphine!” It comes out an excruciating rasp.

I quickly rectify this awful omission. Forty-eight hours later, her agony eased, Janet hands me a cartoon of our tie-tugging encounter. She goes on to create a whole cartoon book for children undergoing stem cell transplants, which the American Cancer Society at once publishes.

MY FIRST GIFT OF PATIENT ART

Janet marries her longtime boyfriend a week before she dies; he changes her diapers between rides as they honeymoon at Disney World. The heroic way Janet lives out her final weeks on earth inspires an elegy: the first poem I’ve written since I was twelve:

Breaking News

In the cancer clinic, people brush us as we seek

the sanctuary of an empty room and visit death together.

You fear not dying but doing it (who wouldn’t?) in diapers.

So off you go, share your final glimmerings out,

allot your two-decades’ treasures, death, like life,

being costly: justly so, two such precious things.

In time you ride, in morphine-trails, your last carousel.

Janet has bequeathed me her legacy of knowing patients with my heart—something quite distinct from any scientific expertise. I come to understand the word that John Keats had written on completing his surgical internship at St Thomas’s Hospital:

“I am certain of nothing but of the holiness of the heart’s affections and the truth of Imagination.”

The true nature of palliative care jumps out at me from the poet-physician’s words. Then I read the words of anthropologist Donald Brown: “There has never been a human culture that hasn’t created art.” Shamans are our oldest artists, our oldest doctors, our psychologists, our priests. The power of their imagery, music, dance, the laying-on of their hands, restores health to countless individuals and communities on every continent, has always done so. I delve int the medicine of pre-Christian Europe—the fifth century BC temples of Asclepius scattered throughout Greece and Turkey—and learn about Asclepius’s dedication to dreams and visions, chanting and dance, which he linked to pharmacy in a marriage of worship and physical healing.

As I leave the Asclepion of Kos, where Hippocrates took shade under the ancient plane as he taught his students the art and science of medicine, a modern-day Asclepian disciple hands me a fresh bundle of sage.

“Hippocratic Tea,” he tells me in fractured English.

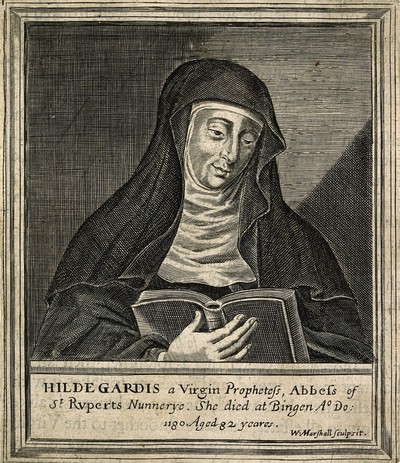

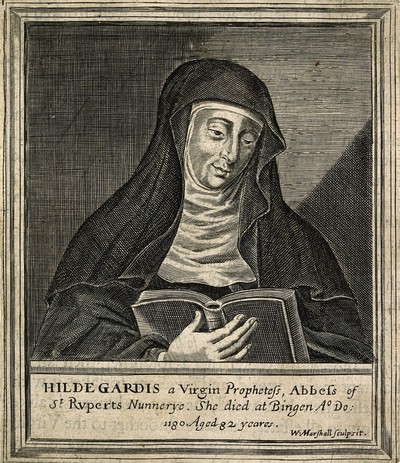

I make a resolution: palliative art must balance curative science. I hear the lyrical 800-old music of Hildegard of Bingen, “A Feather on the Breath of God,” and learn of the abbess-healer’s visions and vespers, how she gathered nuns about her in the monastery she built while writing books that united science with art and spirit.

Hildegard von Bingen, 12th-Century Abbess, Musician and Physician

Line Etching by William Marshall 1642

The 17th century brought an almost complete halt to these ancient beliefs and traditions, with the Cartesian split of body from mind and spirit seeming to totally reject holism and art, anticipating the 18th-century Newtonian view of science as medicine’s tool to fix the human machine. I look about for holdouts and find a glorious one close at hand.

In 1737, William Hogarth donated his “Pool of Bethesda” to my alma mater, where its healing power has graced the stairway to Barts Hospital’s Founders Gallery ever since. The Pool of Bethesda in Jerusalem is thought to have divine powers to heal.

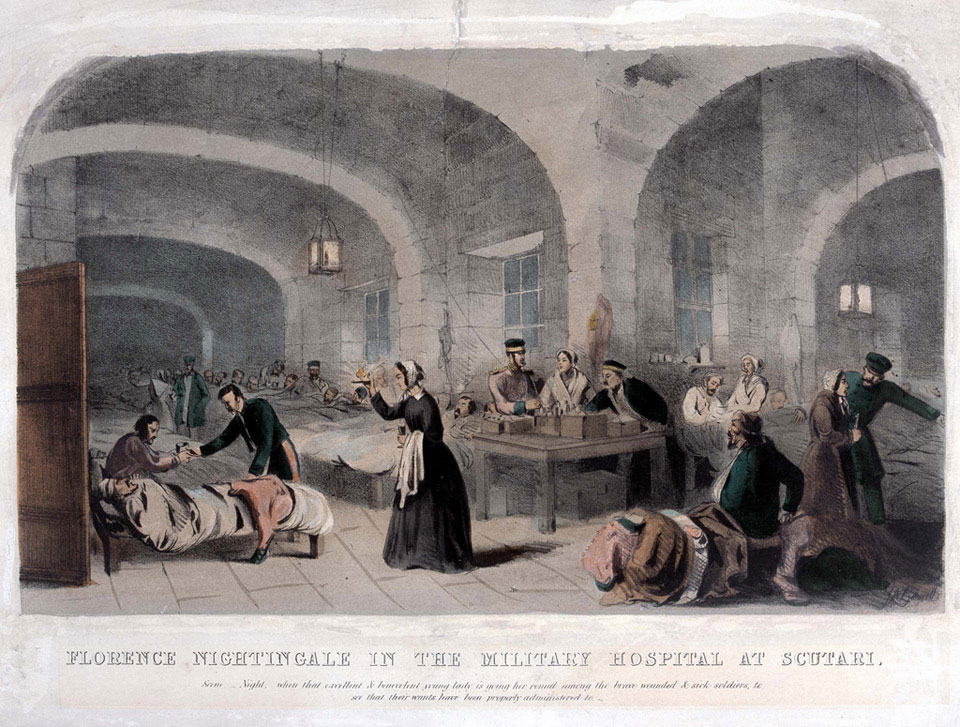

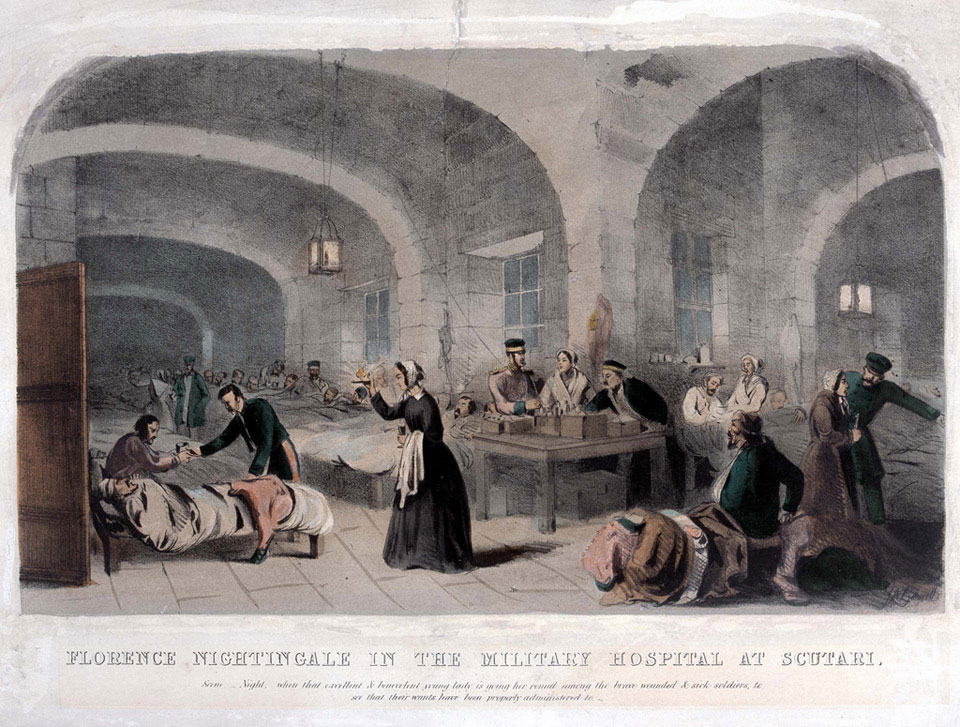

One more epiphany awaits me. Who is it that has stood beside me, guided me, mentored me, from the moment I entered my first hospital ward? It’s the sisterhood of nurses! They’ve never ceased to marry art to science at the bedside since their champion, Florence Nightingale first, declared, as she nursed the gangrenous soldiers of the Crimean War:

I shall never forget the rapture of fever patients over a bunch of bright colored flowers. People say the effect is only on the mind. It is no such thing. The effect is on the body too.

The Lady with a Lamp, London Illustrated News, 1855.

Janet’s bequest hits me full its force: bring art to the bedside! I start to invite artists of every kind into my bone marrow transplant unit.

“I’m not asking you to cure my patients of their cancers,” I tell them. “Only awaken their God-given creativity. Get them painting, writing, singing, dancing. Nothing about cure in that—help them heal.”

Today, the University of Florida’s Center for Arts Medicine (arts.ufl.edu/academics/center-for-arts-in-medicine) gives artists, teachers and students across the globe the chance to learn, research, and advance this art-and-healing mission to all. Whenever or wherever or however it got started, arts medicine is here to stay. It never left, it just took a three-hundred-year sabbatical—or went under cover. I’m very glad it’s back.

Music and Dance Performance, Shands Hospital Bone Marrow Transplant Unit

Along my journey I find an ally. A woman comes to one of the summer intensives our Center’s been holding. Such an ally is she that we’re soon espoused; all good love stories should end in weddings. Together Dorothy and I create HARP: Healing Arts Reconciling People (www.tryhealingarts.com). Our vision? Mend hearts and minds and bodies. HARP may outlive us both, and many younger than us, but don’t we all want to leave a legacy?

Posted by Dorothy Lander: dorothy@tryhealingarts.ca The talented team at This is Marketing (https://www.thisismarketing.ca/) chose a unique colour palette to illuminate

L to R Clockwise: John Graham-Pole aged 2 on Mummy’s knee with sisters Elizabeth, Mary, and Jane, High Bickington, Devon,

Posted by Dorothy Lander Once a month, John Graham-Pole and I showcase the publications of HARP The People’s Press at

HARP The People’s Press released the podcast series Estuary and Piping Plover Find Their Voice to mark two momentous occasions:

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |