Branding: Coordinating My Wardrobe to the HARP Colour Palette

Posted by Dorothy Lander: dorothy@tryhealingarts.ca The talented team at This is Marketing (https://www.thisismarketing.ca/) chose a unique colour palette to illuminate

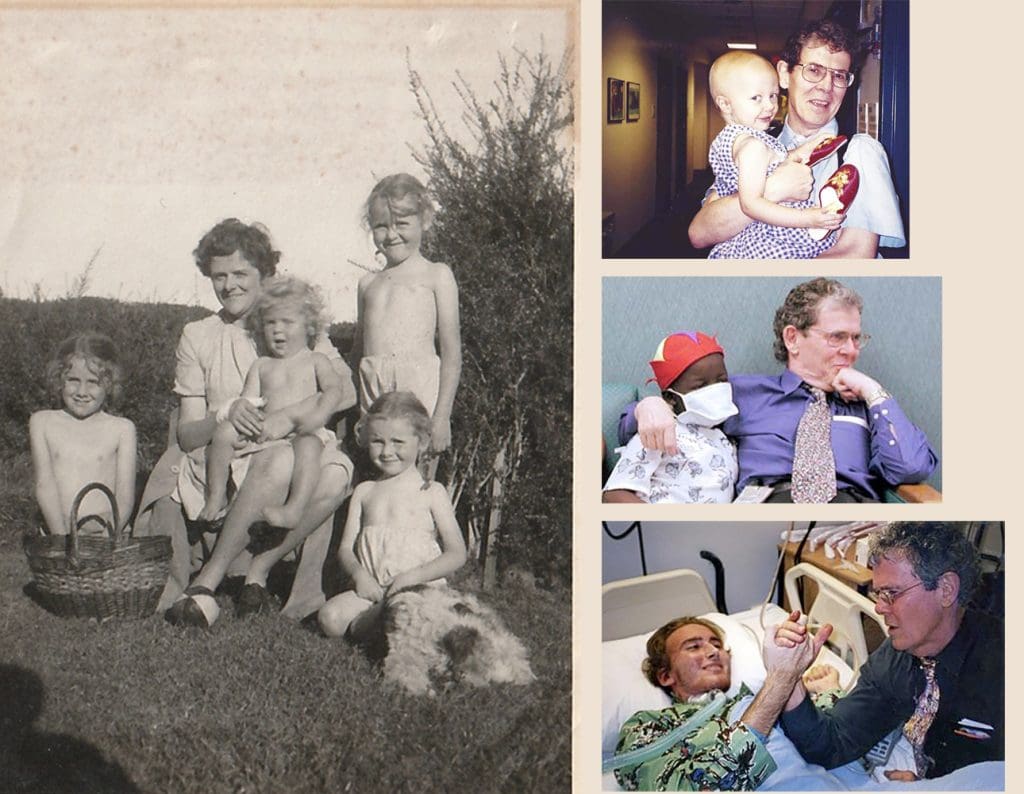

L to R Clockwise: John Graham-Pole aged 2 on Mummy’s knee with sisters Elizabeth, Mary, and Jane, High Bickington, Devon, 1944; John and Bridget, Shands Hospital, University of Florida (UF); John and Roddy, Shands UF; John arm-wrestling with Jarrad after surgery, Shands UF.

Posted by John Graham-Pole

For a caregiver to know if something is healing, we can use data—facts and statistics—and stories—what people actually tell us. Data are the bones of the thing, while stories are the flesh with which we clothe these bones. Stories almost always hold more truth than data.

For me, the best word for close relationships with each other is love. We can call it affection, fondness, empathy, closeness, attachment, kindness, care, but love encompasses all of these. Giving love medicine to a person in need builds a loving relationship. This isn’t in most doctors’ recipe book; when someone comes to us for help, we mostly rely on the biomedical model: taking an objective history of their symptoms and complaints. Important, yes, but loving relationships hold more healing power. Nurses always seem to me more open than doctors to showing love towards to those they care for; maybe it’s just the difference between female and male archetypes attached to the two professions.

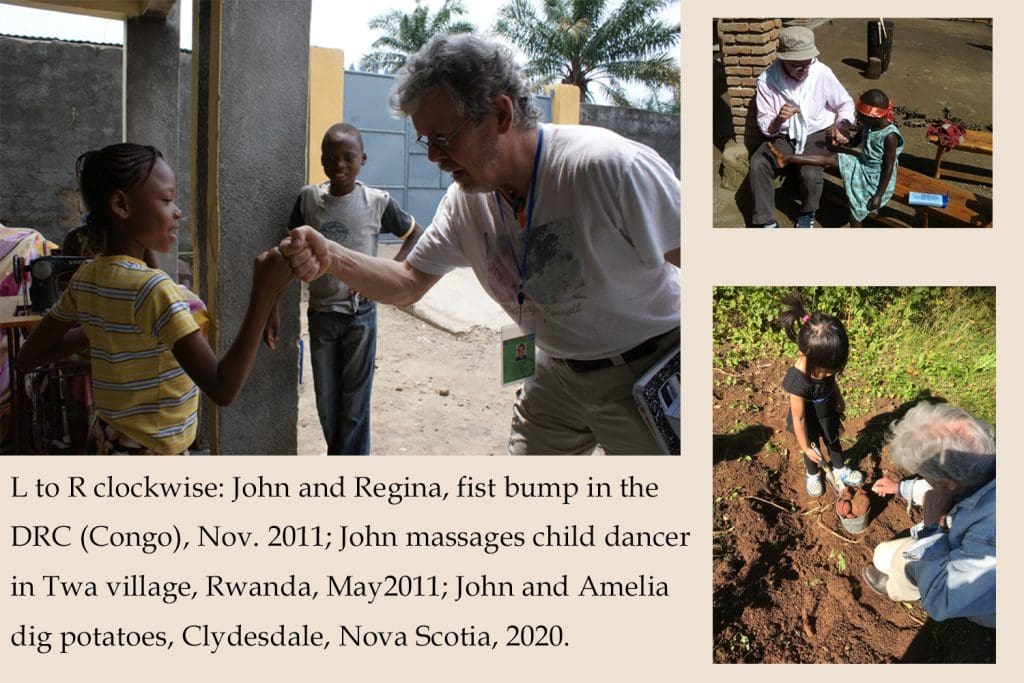

Clown John working and playing with children, Shands Hospital, University of Florida 1990s.

Loving each other comes naturally to us humans—if we let it. Ideally, we offer love to every human and non-human creature that shares our world. This can’t fail to be good for us, but offering such loving presence to another asks of us that we love ourselves. We can all practice love medicine without a license; it’s our heritage. We can use the intelligence of our ears, our eyes, and our hands—all our special senses—to hear and see and feel with full attention. Loving, attentive witness through story and touch offers sensory experience and increases our oxytocin flow, in both receiver and giver. Through physical touch we experience another’s body at the same time as our own. Isn’t it the most natural response to reach out our hand to one who is suffering? “I just want a hand to hold,” a man who was very soon to die told his nurse.

In Louise Erdrich’s 1984 novel, “Love Medicine,” love is the sacred healing art that binds together people and cultures. Early in the book Chippewa Lipsha Morrissey claims his shamanic power: “I know tricks of the mind and body inside out without ever having trained for it, because I got the touch… I got secrets in my hands that nobody ever knew to ask. …The medicine flows out of me. The touch.”

The 1981 New York Times article about yet unnamed AIDS—“Homosexual men dying of an unknown cancerous disease…” was built on human stories. A man shortly to die on ward 5B of San Francisco General Hospital, declared, “I ‘m overjoyed to be part of this community, this haven. I’m on a spiritual high, determined to keep my optimism and humor till the end. With you healers all about me, it should be easy.” Not one of those caregivers was a professional; all were lovers and brothers of the gay community, ostracized untouchables who continued to touch each other with intimacy: Eros and Agape united.

We all yearn to love, often more than to be loved; serving and caring for others gives us abundant opportunity. And we’re also every one of us in need of care, of palliation, of being heard attentively; we can’t get enough of it. Loving attention is as powerful a placebo as prayer, and the giver can gain as much as the receiver.

Here are some personal stories of love medicine. My wife Dorothy remembers when she had her tonsils out at aged six, the church women brought her a candy basket, and her mom gave her a new dress with long ties ending in large yellow daisies. She at once wore it into the maple woods, where she found clumps of hepaticas, which is why the memory endures. Then when her beloved husband Patrick was dying she and her stepdaughter Susan put on a fashion show, their runway being the foot of his bed. Susan wore Dorothy’s clothes and Dorothy wore Susan’s, giving Patrick a huge dose of healing humour because Dorothy stands six foot tall while Susan barely tops five feet.

Before he died of cancer, Patrick bonded with Puss, an affection that proved mutual. Whenever he wasn’t sitting in his kitchen chair, Puss would be curled up on it, sleeping or grooming. When Patrick was home in bed, Puss would climb up on his lap and put her best purr forward; it was like a caress for both of them. The night he died in hospital, he saved some last words to ask after Puss. Next morning at home Dorothy stroked Puss numbly and non-stop. She noticed the cat had stopped sitting in Patrick’s chair, and his absence loomed. Then one day—one of Dorothy’s darker days—she found Puss curled back up on the chair, purring. It was as though she was reuniting Patrick and Dorothy through feline love medicine.

Cendra, the nurse I worked closely with as a palliative caregiver, was sitting one night at the bedside of thirteen-year-old Janice* during her last hours. When Janice began to cry constantly with fear and pain, Cendra climbed in and wrapped her in her arms until she died at peace the next morning. And I sat with sixteen-year-old Ella* for the last thirty hours of her life. Close to the end it felt like we were exchanging breaths. As I leant in among the plastic tubes besetting her, our breaths mingled in a spindrift between us: in her dying she was taking my life to rest, while I lived on, drawing in and exhaling her last cells. Every breath we take—from first inhalation at birth to final exhalation—embodies love medicine.

When an eighteen-year-old patient of mine, Dan*, was on the point of death, his six-year-old sister Joy reached to clasp my hand and ask me: “Is he an angel yet? Are you my friend now?” Then went on to paint her brother’s portrait as she shed her holy tears. And twenty-year-old Karen, after I had run out of magic bullet to offer her, high-fived me, demanded, “Well, let’s at least stay good friends!” Knowing too well the mortal treason of her cancer, she went on to joke, “It’s not dying I mind, doctor, but please not in pampers!” Too soon her fiancé Greg would lift her buttocks, spread her legs, and wrap a fresh diaper in place with tender hands that held such intimate knowledge of her body.

I got to sit at three-year-old Marie’s deathbed. She had resisted sleeping in her own bedroom—scared of something she had no words for—so her mom made up a mattress-bed on the living room floor. Then on the evening of her death, all Marie’s fears dropped away and she announced: “Mommy, I want to sleep in my own room; I want to play with my friends.” Within a few minutes of lying back in her own bed, she cuddled her teddy, sucked her thumb, closed her eyes, and died. Leaving us to ponder the comforting mystery of who those friends of Marie might be. Pretty loving ones, that’s for sure.

Gaelic poet and philosopher John O’Donahue wrote, “As the soul can render the face luminous so too can love turn up the hidden light within a person’s life. Love changes the way we see ourselves and others. We feel beautiful when we are loved, and to evoke an awareness of beauty in another is to give them a precious gift they will never lose.”

*I have changed the names of the children

Bottom L to R Clockwise: Cathy Napier teaching John how to knit, New Glasgow, Nova Scotia; John with Chris England in her 90s, High Bickington, Devon – Chris witnessed Mummy doing jumping jacks while pregnant with John: John with Tareq Hadhad at opening of the Peace by Chocolate factory, Antigonish, Nova Scotia

Love Medicine with Children of the World

Posted by Dorothy Lander: dorothy@tryhealingarts.ca The talented team at This is Marketing (https://www.thisismarketing.ca/) chose a unique colour palette to illuminate

Posted by Dorothy Lander Once a month, John Graham-Pole and I showcase the publications of HARP The People’s Press at

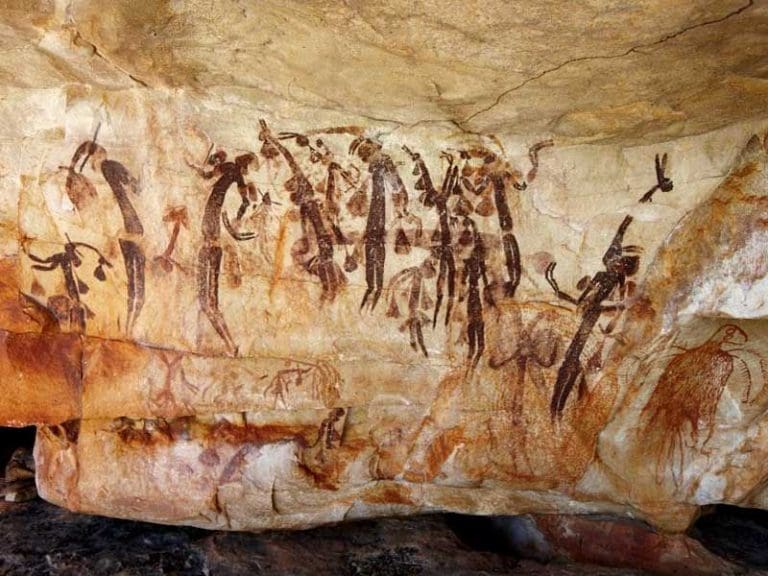

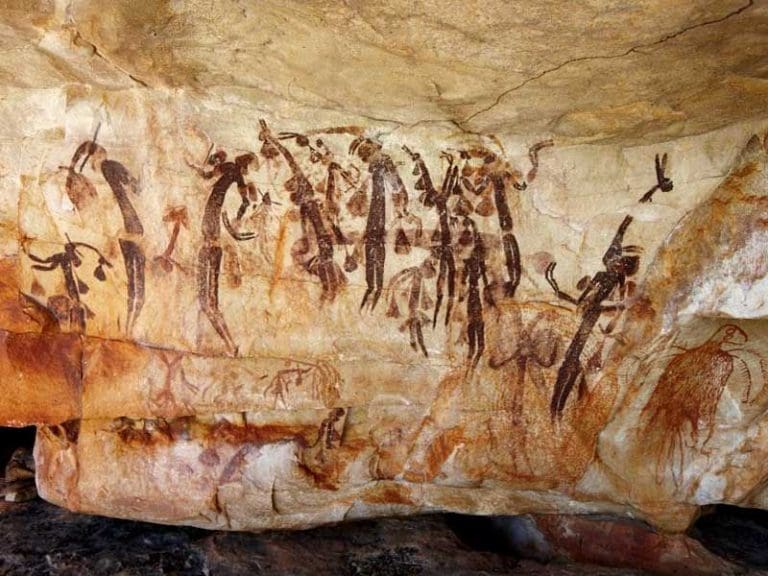

Aboriginal Rock Mural Kimberley Region, Western Australia Posted by John Graham-Pole I don’t have answers to any of these questions,

HARP The People’s Press released the podcast series Estuary and Piping Plover Find Their Voice to mark two momentous occasions:

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |