Branding: Coordinating My Wardrobe to the HARP Colour Palette

Posted by Dorothy Lander: dorothy@tryhealingarts.ca The talented team at This is Marketing (https://www.thisismarketing.ca/) chose a unique colour palette to illuminate

The festive season has John and me remembering the homes that we knew intimately as children. We no longer travel from our home in Nova Scotia to gatherings in family homes – not John’s family in England nor Dorothy’s family in Ontario. We posed the question to each other: can you call up in memory homes that were important to you as a child? Homes where you still can enter every room, moving upstairs and downstairs, inside and outside?

The Irish poet and theologian John O’Donohoe in his book The Invisible Embrace of Beauty encourages us to call up a beautiful image from nature or a beautiful memory “when the mind is festering with trouble or the heart is torn. … There we can find healing.“ Time-travelling to our homeplaces serves as “enduring witness to where our hearts have dwelt — to the places we call home, the “shelter around the intimacy of a life. … You relax and allow yourself to be who you are. The inner walls of a home are threaded with the textures of one’s soul, a subtle weave of presences.”

“Being who you are” also threads through Dr. Gabor Maté’s message in his documentary, The Wisdom of Trauma. “Every human being has a true genuine authentic self. Trauma is our disconnection from it and healing is our re-connection with it.”

Dorothy and John share their experience of time-travelling to their homeplaces as evidence of the healing power of this practice to reconnect with our true genuine authentic self. Dorothy was able to call up many more homes than John as she grew up in a small farming community, where her aunts and uncles and cousins on both sides of the family lived. We were in and out of each other’s homes. John did not have relatives living nearby nor did he have sleepovers with friends as Dorothy did. During his teen years, John was at boarding school (England’s public school system), which he did not think of as “home.”

Dorothy and John will document the weave of presences in their lived experience of home places.

Dorothy: I lived in the same home on the family farm for the first 18 years of my life.

The weave of presences extends beyond Mom and Dad and my siblings June, Howard and David, and our friends and relatives, to the everyday presences of Nature and its abundance. We actively tracked the food supply chain from garden and farm to the kitchen table.

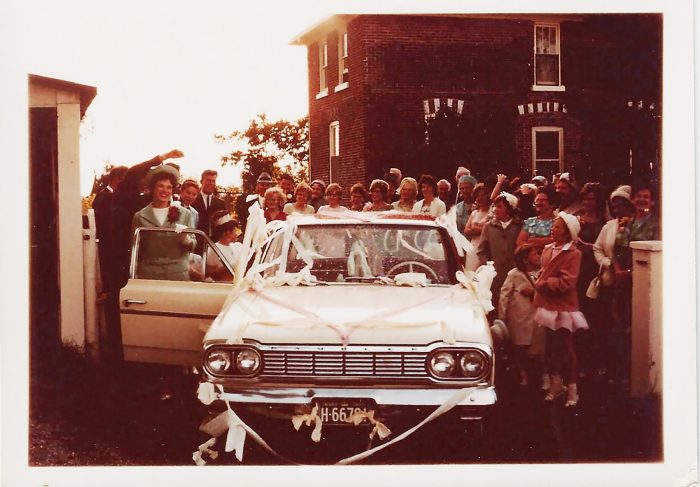

Aug. 28, 1965 – The whole family seeing my sister June and her husband Arnold Bowman off on their honeymoon from the family home.

CD cover prepared by my brother David for Mom’s 90 th birthday celebration, June 9, 2001.

My mother’s signature flower is cosmos. My creative self is inspired by my mother’s practice as a gardener and prize-winning flower arrangements for the Rice Lake Horticultural Society. The ancestral presence of Catharine Parr Traill, author of Canadian Crusoes: A Tale of the Rice Lake Plains (!852) seeped into the inner and outer landscapes of our home. The backwoods where the three settler children, the Canadian Crusoes, were lost, were part of our family farm. Over several successive Sundays, Dad read the story to us at the kitchen table some 65 years ago. The pioneer botanist Catharine Parr Traill was another inspiration for my lifelong practice of Nature Art. My Dad called our view of the backwoods and Rice Lake the “enchanted valley.” We would walk down the hill to the maple woods in spring to see the wildflowers: hepatica, trillium, bloodroot, mayapple. If the timing was right, we would pick the mayflowers (hepatica) for church on Easter Sunday. My rereading of Canadian Crusoes during the pandemic in 2020 spawned my decolonizing memoir, ReReading Catharine Parr Traill, and an unsettling of the white supremacy messages that were read into my very cells as a child.

https://stagingnest.tech/product/book-rereading-cpt/

ReReading Catharine Parr Traill stands as an example of critical reflection on a homeplace, which serves a healing purpose aligned with the Calls for Action in the 2015 report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada.

Many other beautiful memories of my growing-up home connect me to my authentic self:

My dad was fun-loving. For April Fool’s Day, he came in from the barn just as the rest of the family was beginning to stir and announced loudly. “Look out the window – the Jackson’s donkey is coming down the road.” We all rushed to look – no donkey. April Fool’s. The Jackson’s on the neighbouring farm had a donkey to keep the coyotes away from their sheep. I knew this donkey (named June) well as my best friend Brenda Jackson and I were at each other’s homes throughout our growing-up years.

Our home had no central heating. We kept warm in the winter with hot water bottles and heated irons in our beds – My parents, my sister and I slept upstairs; the boy’s bedroom (as it was known) was downstairs right next to the kitchen and the wood stove. Everything took place in our small kitchen, which housed the wood stove, the kitchen table, and eventually a television, which came late to the Lander family. (My father promised us teenagers we would get a television, when it was in colour, thinking that would never happen!) The value of thriftiness was drilled into me at an early age. My mother operated the washing machine in the kitchen, heating up the water on the stove. It so happened that we also boiled down sap to make maple syrup on the wood stove. My mother didn’t realize that she had poured the hot sap into the washing machine, until she went to take the sugar-encrusted clothes off the line.

In moments of loss and sadness and feeling stressed or overwhelmed, beauty can always reach out and touch us, often in the form of memory of homeplaces. In 2023, I lost two beloveds from my childhood: in January, my oldest first cousin Leighton Westington, aged 91 and in December 2023, Brenda’s mother Joyce Jackson aged 94. I find solace in beautiful memories of them in their homeplaces.

The Jackson home was a second home for me, and I got to do things with Brenda that would never happen in the Lander home. Brenda and I got to watch the Late Late Show on Television out of Channel 7 WKBW Buffalo until the sign off by Mahalia Jackson. Joyce and Ed hosted dance parties at their home. Dancing was forbidden at my home. With Brenda at the piano, we would sing pop songs together. We always had butter in the Lander home but the Jacksons, who did not have cattle, used margarine. A small precious memory: Joyce melting the colouring packet over the pilot light on the stove and mixing it into the margarine.

My Aunt Ada and Uncle Frank moved out of the Westington century home, a stone house, when Leighton married Fran in 1958. Their home had a dumb waiter, the first I had seen, and I loved to see it in operation, transporting food and other necessities from the basement to the kitchen. As a teenager, I was babysitter for Leighton and Fran’s four girls. I am the youngest in my family and have not been a birth mother so I carry my memories of my times with these four little girls as my sole life experience of playing and learning with children for an extended time. A healing homeplace memory.

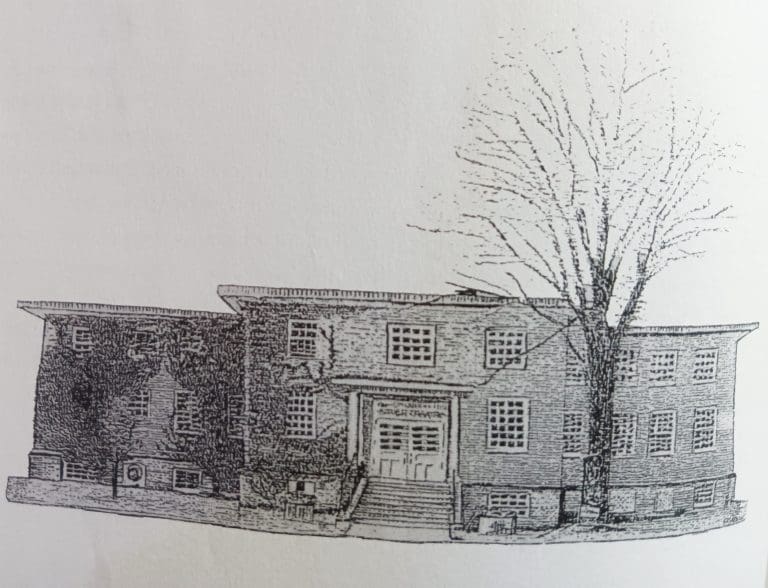

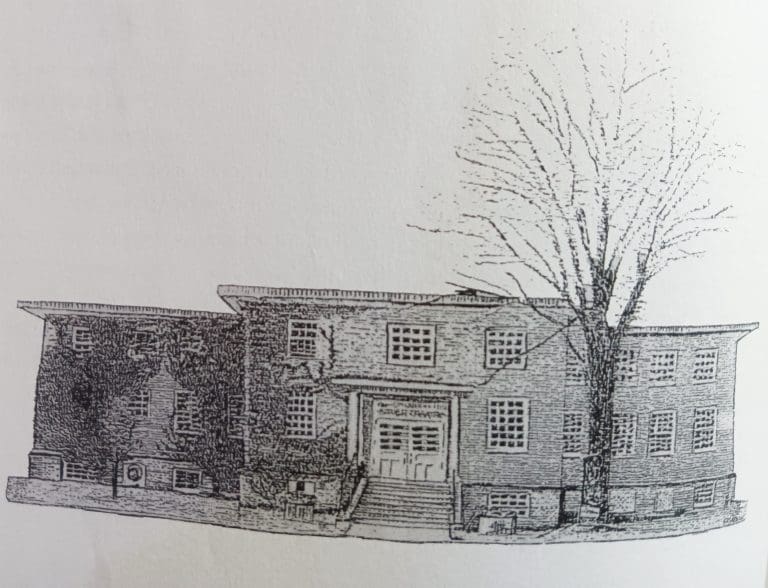

I had completed a “final” draft of this blog entry when I realized that I must have blocked the memory of my 5 year-old self when I was separated from my mother and my childhood home. The childhood trauma that disconnected me from my authentic self happened in 1952 when I started school (S.S. #16 Plainville). At the very same time, my mother went into hospital for an emergency hysterectomy and was in care there for several weeks. My brother David and I (the youngest) went to stay with Aunt Flo and Uncle Jack and my two cousins John and Blayne. June and Howard stayed with Dad. That was the one year when all four of us were at school together so I saw June and Howard at school but I did not see Dad or home. A few details of Aunt Flo’s home have stayed with me: the breakfast nook featured a wall bench and a fold-out table top that was hooked to the wall after breakfast; the Venetian blinds on the living room windows; and Aunt Flo’s signature plant, the sweet pea.

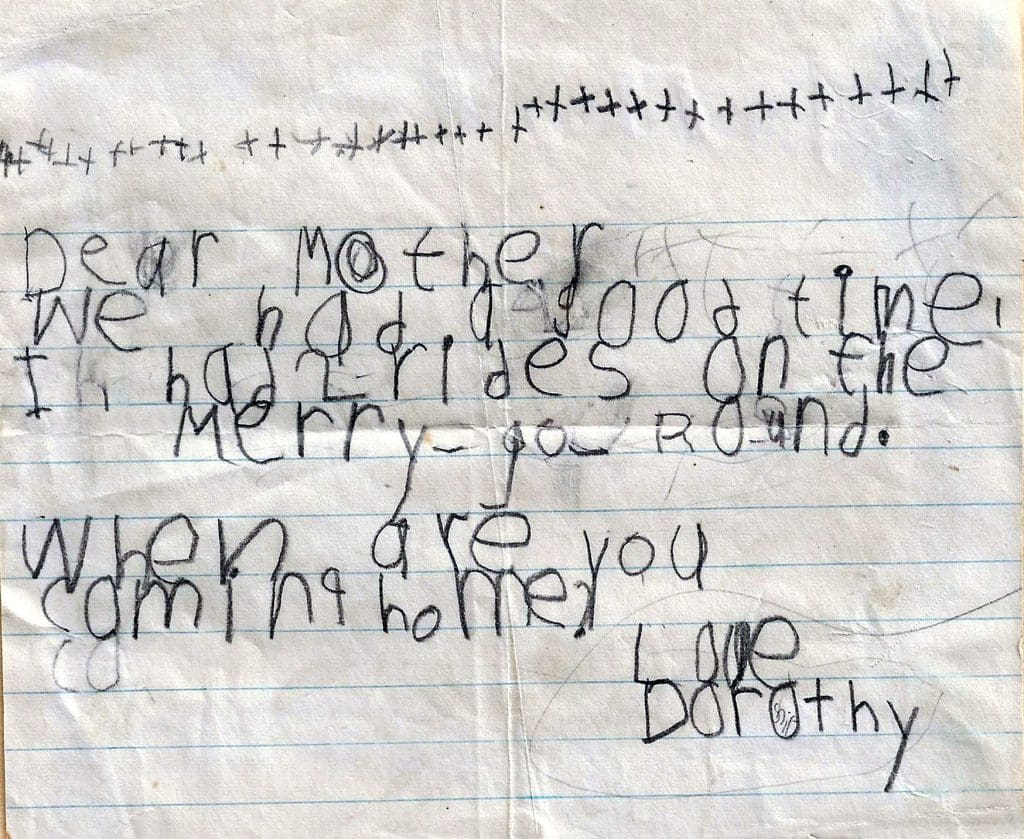

My letter to Mom in hospital connects trauma to home. The plaintive last line: “When are you coming home?” (5 years old and I could even print question marks!) Aunt Flo also wrote letters to Mom in hospital, among which she tells her how I came home from school with soiled clothes. I was too shy to put up my hand to go to the washroom and regularly peed my pants that first year of school.

This summer I planted sweet peas in our Clydesdale garden with Aunt Flo in mind. They had foliage in abundance right through the first frosts. But nary a flower – was I communicating my childhood trauma to my plants?

I could go on and on but now it’s over to John.

John:

I have less vivid memories than Dorothy of the houses I grew up in. Perhaps it’s because I didn’t live for very long in any one of them. “Dobbs,” as it was called, is the house my parents moved to when my dad bought a medical practice in the ancient village of High Bickington in North Devon. Dorothy and I visited Dobbs early in our marriage and the current owners let us in to look around.

We visited Christine England, who was then ninety-nine; she had lived in the village all her life. She had a clear memory of Mummy doing jumping jacks at the Women’s Institute Hall when she was far along in her pregnancy with me, while I was bouncing up and down inside her!

One stirring memory was of my dad’s surgery (more often called “office” in North America), where he saw his patients early in the morning before setting off on his rounds of the nearby villages and hamlets in his racing green MG sports car. His patients would enter by the back door and hang their coats and hats on a peg outside the surgery. I hold onto a very early memory of spying on him through the partly open door where he was examining a young teenaged girl and lecturing her mother, presumably about what she needed to do for her daughter to keep her healthy.

I was probably only three when our parents divorced and my mother moved us four children up to Weston-Super-Mare on the Somerset coast to be near my grandparents, who supported her financially, because she never worked outside the home after her marriage. We lived in two houses in Weston, called respectively St. Martin’s and Ravenswood (I think it’s still a British custom to give our homes names). We lived in Ravenswood for about six years before my mother’s death, and I have fond memories of my friends always gathering at our home before we tramp walked to school about a mile away (no school buses in those days!). I had my own bedroom next to my mum’s, and on Saturday mornings I would often wake to find “Buster” Bill Harris, my Mum’s boyfriend, sleeping on a mattress on the floor. Where he started out the night I never discovered but I hope it was in Mummy’s bed. A nice memory.

It’s this house that is the one I remember most vividly from childhood, perhaps because there were such happy years before my mother’s untimely death at fifty-one. We would have family get-togethers in the sitting room (called very grandly in the English parlance the “drawing room.”) Mummy would play the piano and we four would gather around her and sing “The Skye Boat Song” or “Loch Lomond.” Not sure why we always sang Scottish songs but that’s what I remember. I remember there were French windows that opened out onto a veranda where my mother grew wonderful hollyhocks. Being the youngest and the only boy in the family I loved to respond to my mum’s and, increasingly, my sisters’ requests to fetch something from the kitchen or the dining room or one of the upstairs bedrooms. How I loved to leap three steps at a time up the stairs!

I don’t have very good memories of my Uncle Ken and Aunt Joan’s house in the West Riding of Yorkshire where I and my sister Jane moved after Mummy’s death. Looking back, I realize I was totally numb and never shed a tear throughout my teenage years. Also, I was away at boarding school much of the time. I didn’t make any close friends in Yorkshire, which for me was an alien country to this boy from Southern England with his “BBC” accent, thanks to the elocution lessons my mother had insisted on my having. The North-South divide was very clearly defined—and still is to a considerable extent.

A Conversation: Our Clydesdale Home

Dorothy: John, you told me that you have now lived in our home in Clydesdale, Nova Scotia, longer than any other home. And that you now feel that this is home. Can you say something about how our home allows you to be who you are – to re-connect with your authentic self?

John: What lovely images here of both the outside (our new solar panels) and inside (leaning together on “the ark.”) I’ve lived here almost seventeen years, which is far longer than any other home, but it did feel like I’d “come home” very soon after I came to live here. I think it goes right back to those earliest days when I lived out in the country like now, after living in cities throughout the intervening sixty-plus years. I’m clearly a country boy at heart, though on reflection I think we are much more likely to connect with our authentic selves in rural settings, rather than the hustle and bustle of the big city.

But it also has to do with my being retired and getting older and slowing down, and spending every day right here, rather than our home being simply a place where I laid my head between long and taxing days at work. I have taken to sitting to meditate for short periods in the morning, and I am very aware of everything I can see in kitchen/living room, and how it came to be here. And what a special delight it is to wake every morning to the sight of our Japanese maple (beautiful at all times of the year) immediately beyond our window beyond the foot of our bed.

Dorothy: Your mention of the Japanese Maple and “the Ark,” weaves the ancestral presence of Patrick into our Clydesdale home. It was the death of my husband Patrick Napier in 2004 and my quest for healing that brought us together. Patrick and I planted that Japanese Maple in front of the picture window, thinking it was a shrub, not the roof-high tree that it has become. The Ark is the Napier name for our kitchen island, transformed from the heritage sideboard that came across the sea from Ireland in the late 19th century. I drove from Antigonish to Gainesville, Florida in July 2005 to take the three-week summer intensive with the University of Florida’s Center for Arts and Medicine, which you co-founded, hoping to learn about the arts and end-of-life care. This was the beginning of our collaborative research and practice in the healing arts – and the beginning of love. The kitchen photo also reminds me that we often call on Patrick’s counsel and apologize when we disrupt his kitchen, say, getting the containers on the spice rack out of alphabetical order.

Finally, lest our blog readers think that time-travelling to homeplaces is just for our generation, we can report that when we suggested this blog entry to our twenty-something website coordinator Alexandra Chapman from This is Marketing, she responded immediately with her own experience of a healing home. Just the week before, when she had been talking to her mother in New Brunswick about being overwhelmed, they addressed this by imagining themselves at the family cottage, their slowing-down refuge from their busy lives.

Synchronicity yes, but more than that, a signal that everyone has a memory of a homeplace that nourished their authentic self. We need only ask.

Posted by Dorothy Lander: dorothy@tryhealingarts.ca The talented team at This is Marketing (https://www.thisismarketing.ca/) chose a unique colour palette to illuminate

L to R Clockwise: John Graham-Pole aged 2 on Mummy’s knee with sisters Elizabeth, Mary, and Jane, High Bickington, Devon,

Posted by Dorothy Lander Once a month, John Graham-Pole and I showcase the publications of HARP The People’s Press at

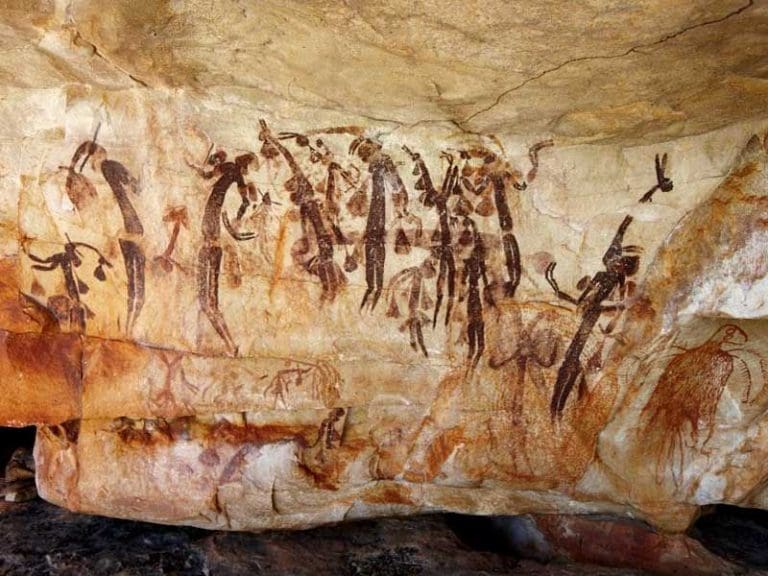

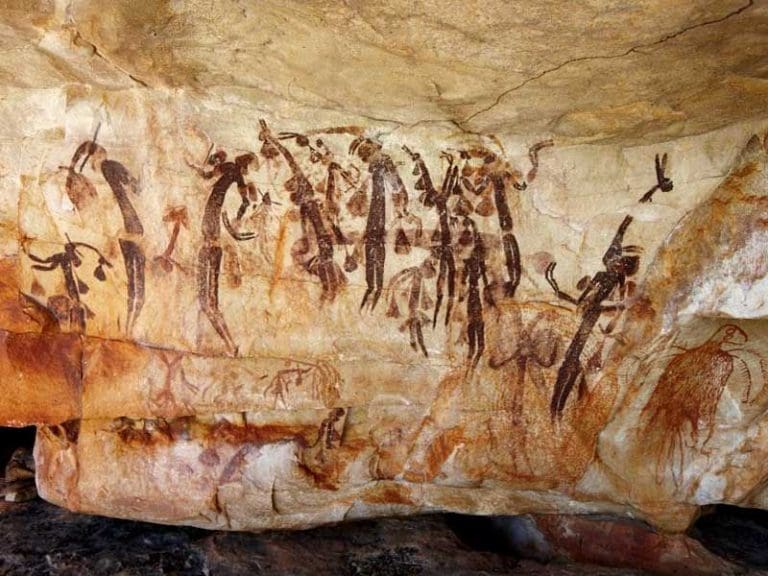

Aboriginal Rock Mural Kimberley Region, Western Australia Posted by John Graham-Pole I don’t have answers to any of these questions,

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |