Branding: Coordinating My Wardrobe to the HARP Colour Palette

Posted by Dorothy Lander: dorothy@tryhealingarts.ca The talented team at This is Marketing (https://www.thisismarketing.ca/) chose a unique colour palette to illuminate

My Complicated Relationship with the Burdock: Revered or Reviled?

Growing up on the family farm in southern Ontario in the 1950s and 1960s, I became acquainted with the burdock (Artium lappa) as a noxious weed, an invasive plant that caused problems for livestock and crops. The common burdock is a biennial weed, reproducing from seed. Indeed, one plant can produce between 6000 to 16,000 seeds. The tiny, hooked slivers on ripe burrs can get into an animal’s eye and cause infection. And animals covered with burrs can reduce market value as farmers are not willing to bring more burdock seeds into their operation.

One of my chores was to dig up burdocks right to the end of the long taproot, and then to feed it to the pigs. I learned very early that our pigs were vegan and would eat just about any vegetation. Their burdock delicacy came complete with a dirt garnish. And they thrived — Dad was proud of his Grade A pigs. Along with my three older siblings, we were walking testimony to the sticking power of those “hitchhiking” burrs on our clothes or worse, in our hair.

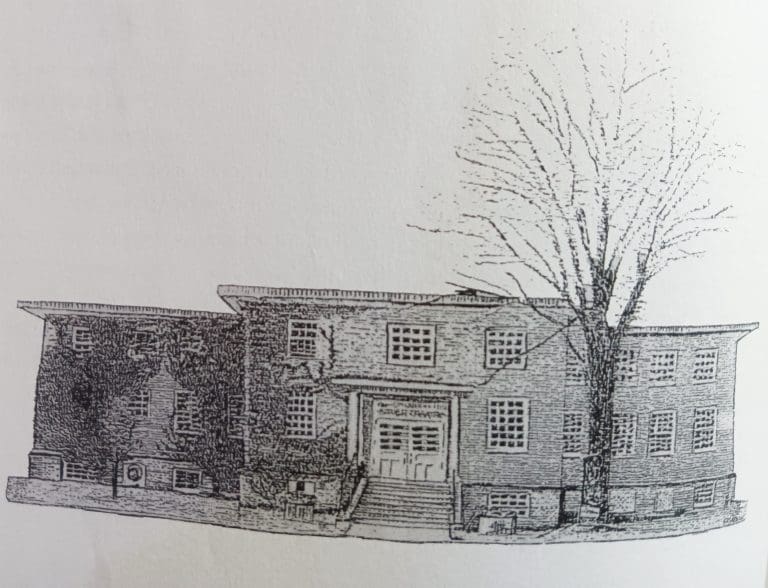

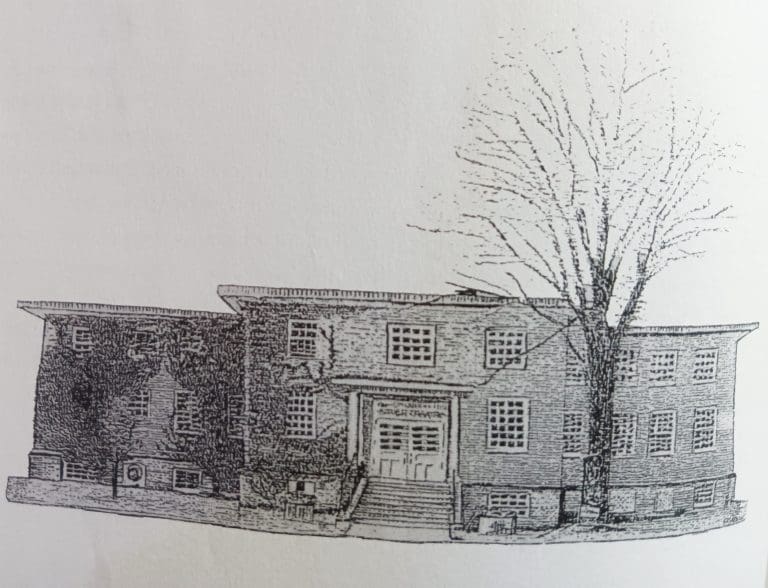

Not just chores, I was also introduced to burdocks as a disciplinary measure. Naughty children in the 1950s and 1960s in Ontario were well acquainted with the strap, including my two older brothers; one teacher even had my bro wet his hands so the strap would hurt more. My mother, who was principal and teacher for a two-room schoolhouse in Bewdley, Ontario had a more practical plan; student discipline took the form of digging up burdocks. And no danger of running out of a supply, as the seeds remain viable in the soil for up to 10 years.

My other childhood memory of burdock may have presaged my propensity for using Nature’s art supplies. I remember creating stick-together human and animal figures and open-plan houses and fortresses by hooking one seed pod to another. A distraction from my digging assignments perhaps?

Years later in the mid-1970s, when I took up occupancy of a small plot of land in rural Nova Scotia near Antigonish, my relationship with the burdock was still more reviled than revered. The burdock loves fertile, moist soil and thrives on the fossilized horse dung in Clydesdale, Nova Scotia, dating to the early 20th century when John Henry Callaghan built the farmhouse and farmed the land where I live. My battle with the burdock continues to this day, as shown in the photos. No burdock finds its way to the compost pile but instead I carefully deposit my diggings in the green bin to go to the landfill.

In recent years I have become uneasy with my lifelong contempt for the burdock—how to reconcile this with my growing awareness of the gift plants offer to the survival of humanity and Mother Earth itself? We are learning from Indigenous people, exemplified by Robin Wall Kimmerer in Braiding Sweetgrass, that as part of the covenant of reciprocity, we are obliged to give thanks to plants and animals when we disturb them and take their lives, and then to return the gift. And to acknowledge that just as we love Mother Earth, Mother Earth loves us. I have begun to have conversations with the burdocks that I dig up and the other species that I disturb, such as the earthworm that was sharing the deep soil with the burdock, as seen in the hole in the first photo. I explain to the burdocks that they are competing with the pumpkins that are growing in this rich soil and that removing them will not end their life – you will grow and flourish in the landfill along with many other burdocks that I have sent that way. I congratulate the burdock as the inspiration for Velcro. In 1941, Swiss chemical engineer George de Mestral was walking in the Alps and pulling burrs from his dog’s fur and his wool pants and was inspired to invent a practical alternative to laces and not a weapon of mass destruction like so many inventors were focused on in those war years. As for the earthworm, I shun violence and try not to cut them in half. I know that s/he will not create two earthworms and even if s/he does survive, s/he will not flourish.

To further complicate my relationship with the burdock, John, the other half of our low carbon couple, recalls his childhood experiences with burdock associated with hospitality and herbalists. While I was battling the burdock in the back forty, teenager John was living in Yorkshire with Uncle Ken and Auntie Joan where he moved after his mother died in Somerset when he was 12. These years were painful for John but recently he has been recalling the learning moments and relationships with his mother’s family. His travelling doctor Uncle would take him along on his visits to mining families; miners in those days suffered from black lung. John remembers Uncle Ken and Auntie Joan taking him along in their Ford Anglia to visit a Mom-and-Pop shop in Fitzwilliam, Yorkshire, where the shopkeeper proceeded to dole out carbonated burdock-dandelion beverages and Pontefract cakes – no charge. This was more than hospitality—the shopkeeper and his family were Uncle Ken’s patients and these Yorkshire specialties were in-kind payment for services rendered. Both the burdock-dandelion drink—a soft drink like root beer, strictly a British thing— and Pontefract cakes—a licorice sweet stamped with Pontefract castle and also called the Yorkshire penny—are steeped in history.

The earliest record of a Dandelion & Burdock drink is from c. 1265, from an account of St. Thomas Aquinas, who prayed to God for inspiration as he walked into the countryside, where he made a drink with the first plants that he found: dandelion and burdock. The apocryphal additions to the story claim that Thomas took this walk during a bout of writers’ block; he developed a thirst and put his trust in God to provide. And so it was that he made a drink from the first plants he came across. It was this first burdock-dandelion drink that aided his concentration when seeking to formulate his theological arguments that ultimately culminated in the Summa Theologiae.

As for Pontefract cakes, Britain’s oldest sweet, liquorice’s (Glycyrrhiza glabra) arrival in Yorkshire dates to around the 11th Century, when monks or Crusaders first brought the medicinal Mediterranean root to the county. By the early 18th Century, Yorkshire’s imposing fortress—Pontefract Castle—was transformed from medieval keep to apothecary storeroom. By 1720, as demand shaped the local economy for medicinal liquorice (at the time physicians used it as a cure-all for everything from stomach ulcers and heartburn to colic, bronchitis and tuberculosis), the castle was rented out and roots were stored in the castle dungeons instead of weapons, gunpowder and prisoners. In 1760, George Dunhill, an apothecary chemist in the family trade in Pontefract added sugar to liquorice (then a dissolvable, medicinal pastel) to create the chewable non-medicinal lozenge, the sweet known today. The image of Pontefract Castle remains stamped on this sweet.

Burdock bitters were part of the medicinal arsenal for both Uncle Ken and John’s doctor father and any other rural doctor in those days. Burdock was brought into play to cleanse the blood, cure snake bites, stop acne, and to treat stomachache and joint swelling.

These days, when I google burdock, the first hits are its health benefits and tips on how to cultivate and harvest it.

I can only imagine my father’s horror at the very idea of “The Complete Guide to Plant, Grow and Harvest Burdock” and a site selling “Heirloom Seeds.”

Health benefits:

It’s a powerhouse of antioxidants

It removes toxins from the blood

It may inhibit some types of cancer

It may be an aphrodisiac

It can help treat skin issues

It acts as a diuretic

It reduces inflammation

It has digestive benefits including alleviating constipation and increasing helpful bacteria in the colon.

It defends against diabetes

Finally, I began to wonder if there was any shift among cattle ranchers and farmers about burdock. This …

The Hobby Farms web site names the burdock as one of five weeds that heal the soil. https://www.hobbyfarms.com/5-weeds-actually-helping-your-soil-2/

From a biodynamic perspective, all weeds are beneficial to the soil in some way. They have different ways of fixing nutrients into the soil. They give us information about our soil, and when we learn their language, we can easily look over a property to understand its deficiencies and problems without breaking ground.

If left alone, there’s a progression of weeds in Mother Nature’s arsenal that restores soil health and balance. She can afford to be more patient than we can. If you can strike a balance with your garden that allows some of the work to be done by these experts while ensuring light, air and nutrition for your fragile annuals, you will be a truly successful gardener!

I’m now learning to listen to what the burdock is telling me about the soil. Burdock indicates low calcium, high potassium soils. Weeds with deep taproots such as dandelions and burdock indicate compacted soil lacking in water, air, and nutrients. Burdock indicates low calcium and manganese, high in iron, sulfate and potassium soils.

This is the affirmation that I needed. My conversations with the burdock—learning their language—serves to strike a balance in my complicated relationship.

Posted by Dorothy Lander: dorothy@tryhealingarts.ca The talented team at This is Marketing (https://www.thisismarketing.ca/) chose a unique colour palette to illuminate

L to R Clockwise: John Graham-Pole aged 2 on Mummy’s knee with sisters Elizabeth, Mary, and Jane, High Bickington, Devon,

Posted by Dorothy Lander Once a month, John Graham-Pole and I showcase the publications of HARP The People’s Press at

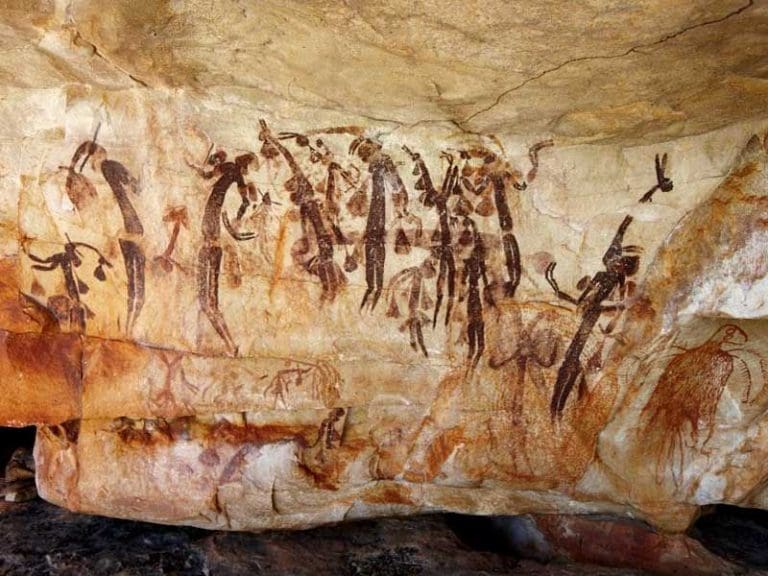

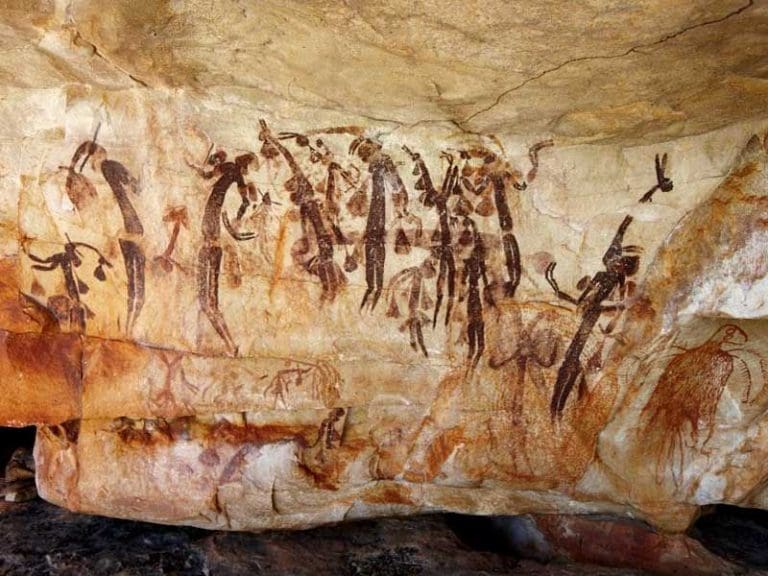

Aboriginal Rock Mural Kimberley Region, Western Australia Posted by John Graham-Pole I don’t have answers to any of these questions,

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |