Branding: Coordinating My Wardrobe to the HARP Colour Palette

Posted by Dorothy Lander: dorothy@tryhealingarts.ca The talented team at This is Marketing (https://www.thisismarketing.ca/) chose a unique colour palette to illuminate

Every so often, my past life immersed in academic research has relevance to publications for our healing art press HARP Publishing The People’s Press (www.harppublishing.ca). Some 20 years ago I developed a qualitative research method of appreciative genealogy, based on postmodern philosopher Michel Foucault’s ideas of “a history of the present,” as a way to situate contemporary practices in historical context.

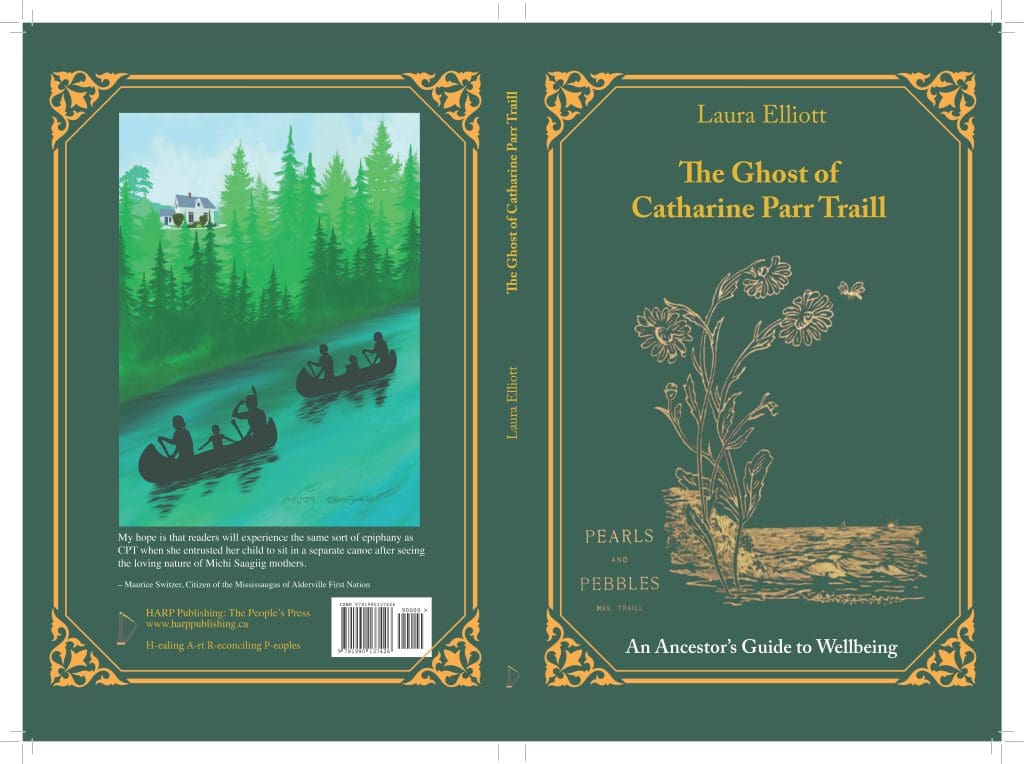

On July 16, 2023, at Christ Church Community Museum in Lakefield, Ontario, HARP launched Laura Elliott’s The Ghost of Catharine Parr Traill: An Ancestor’s Guide to Wellbeing, which situates present-day wellbeing practices in the context of 19th-century Indigenous-Settler relations.

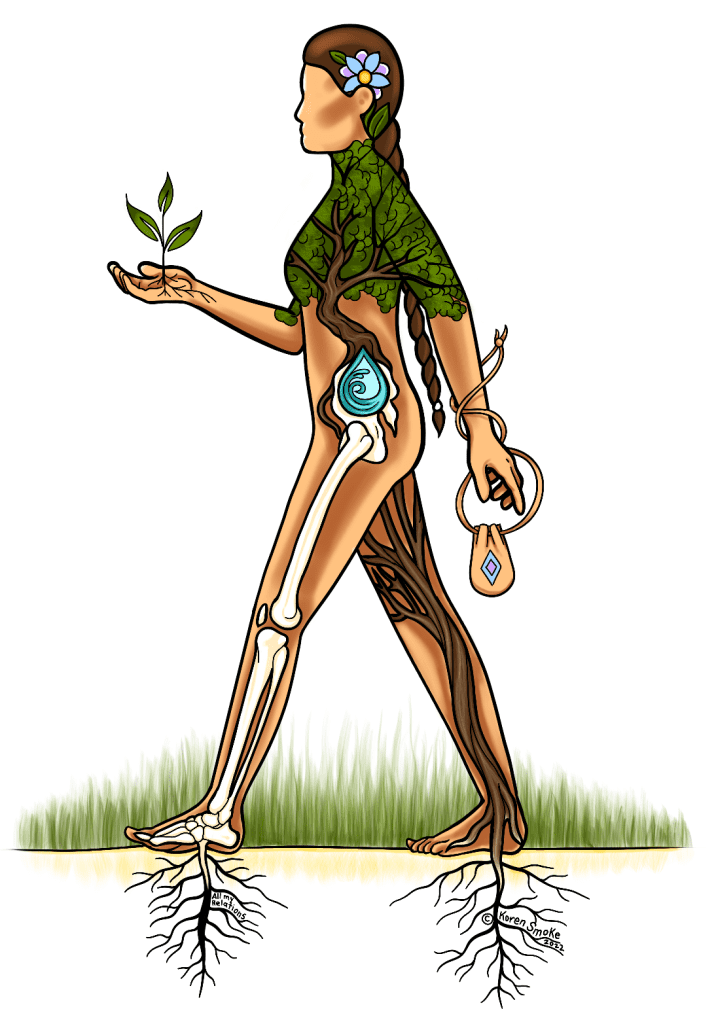

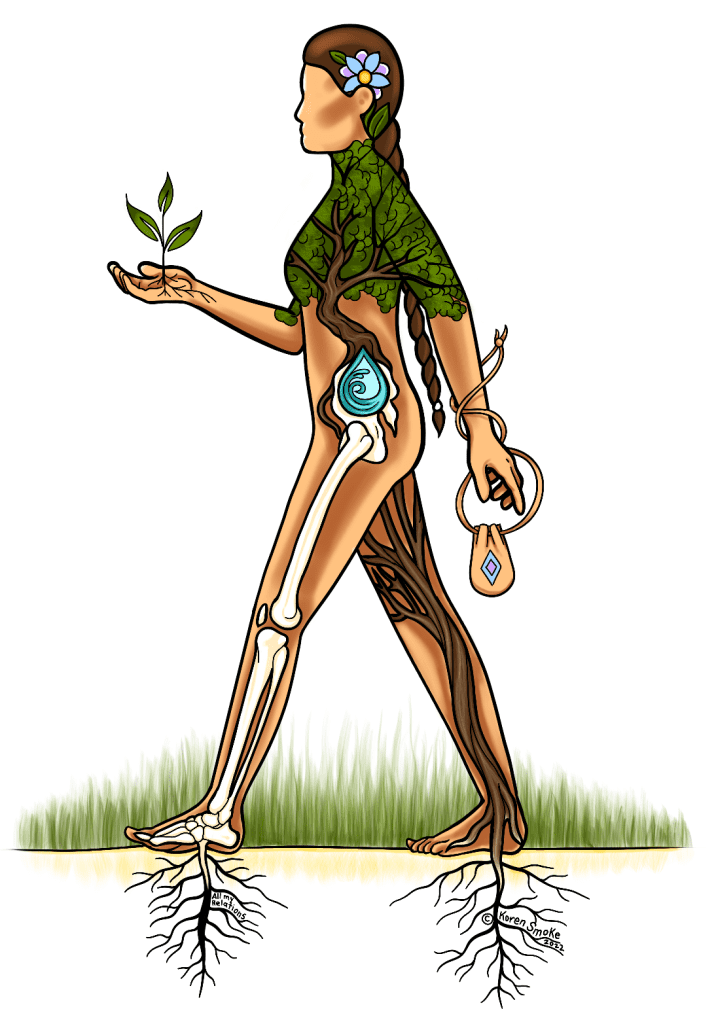

After readings by Laura and myself, and introducing Anishinaabe artist Koren Smoke, I engaged Laura, Koren and myself as publisher in a shared inquiry into Koren’s cover art. My purpose was to trace the forces that gave birth to our present-day practices of wellbeing; and to identify the historical conditions upon which they depend. As we three women represent quite different cultures (Koren was wearing a traditional ribbon skirt she had made herself), different generations, and different life experiences, I wanted us to use the historical materials, including our personal histories, evoked by the book and its artwork to rethink the present.

Photo: Ali Janssen

I did not inform the audience of about fifty people ahead of time of my intention. So few would have any idea that they were witnessing a well-planned inquiry. But I had presented my plan to Laura and Koren in advance:

Dear Laura and Koren:

I want to share with both of you how I plan to introduce our three-way shared inquiry that will focus on Koren’s cover art. It is great that we will be grouped informally in three chairs. I want to draw attention to our grouping—transgenerational and transcultural—and how we represent “two-eyed-seeing” (Mi’kmaw Elder Albert Marshall’s expression for the co-learning journey that draws together settler and indigenous knowledge for the benefit/wellbeing of all). And then onto what each of us “reads” into the cover art, which broadly takes up Maurice Switzer’s words about the loving nature of Michi Saagig women caring for Catharine’s child. I know from ReReading Catharine Parr Traill that you, Koren, welcome individual interpretations of your art; so how would it be if I held up your All My Relations image as an example of my immediate reading of this image?

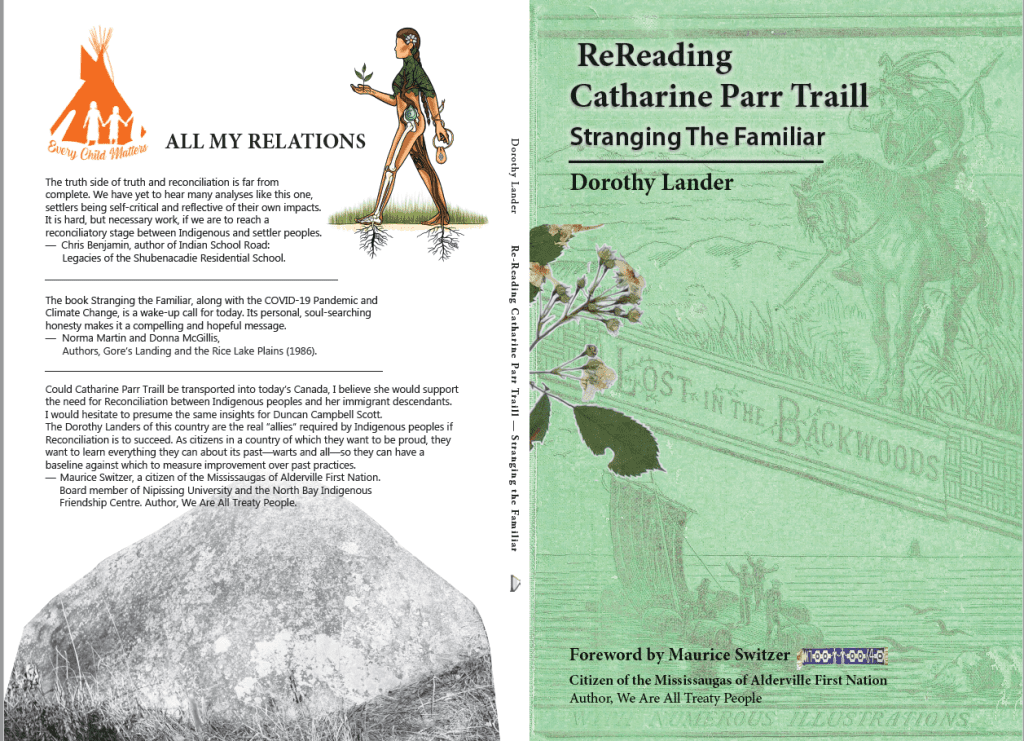

On the day, I introduced the inquiry by describing how I interpreted this image as Koren re-imagining the Mohawk girl in Catharine Parr Traill’s (1852) children’s adventure story, Canadian Crusoes: A Tale of the Rice Lake Plains, as the rescuer, not the rescued: she was the healing force who shared her gifts of Indigenous knowledge, Indigenous medicine, and Indigenous crafts with the three settler children, enabling them to survive and flourish. Koren’s response to Dorothy’s interpretation forms her Artist’s Statement in ReReading Catharine Parr Traill: Stranging the Familiar (p. 14).

All My Relations goes deeper than human interaction. All my relations to the earth, flesh, bone, animals (shown in the leather medicine bag on the side of the heart), plants and our sister the water.

You may interpret All My Relations as Indiana in Canadian Crusoes. It’s a perfect fit and meant for many interpretations.

Photo: John Graham-Pole

It was Koren who initiated our inquiry by describing her process in creating this image. We had not talked about my research methodology, nor even uttered the phrase “a history of the present” before the launch, yet here was Koren amplifying that very meaning:

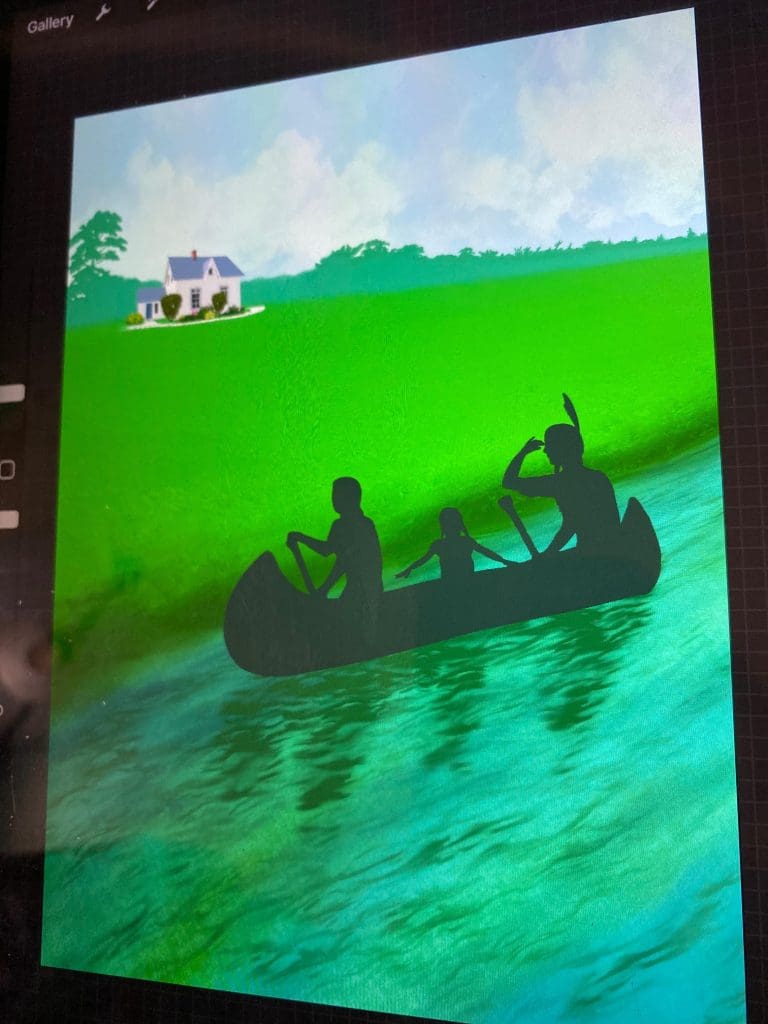

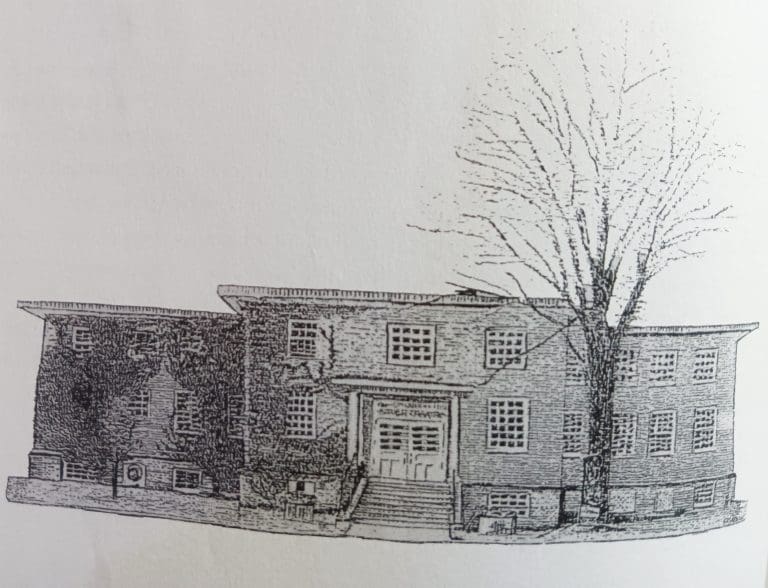

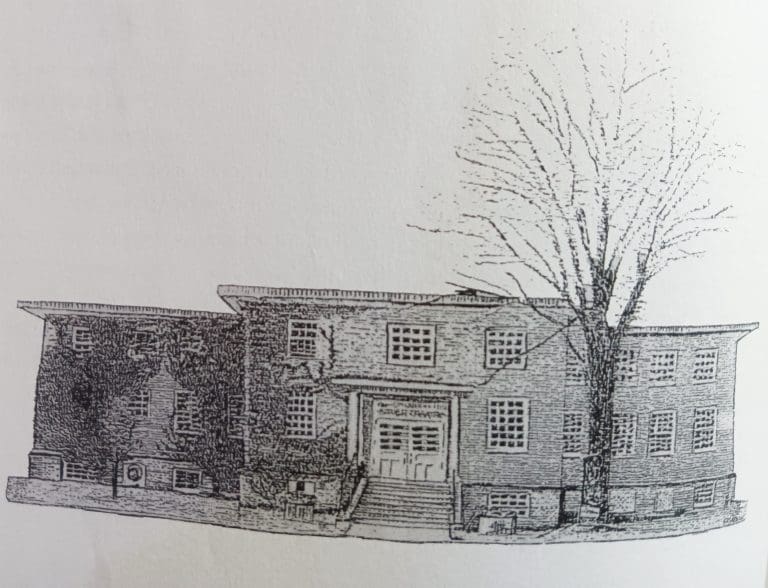

The process of the image for the back cover was to show the cut scene of Catharine Parr Traill’s home in present day which is now Laura Elliott’s current home. Through the greenery and a journey to the past you see the Michi Saagiig women paddling and steering the canoes, and a visible settler woman in the front of the second canoe, with her child in the middle of the two Michi Saagiig women in the first canoe—showing the trust Catharine had for the local Indigenous women who also carried the knowledge of the land and understood the navigation of the canoe and the water. The colour scheme of light emerald was a nod to Dorothy’s cover of her book Rereading Catharine Parr Traill: Stranging the Familiar. I chose to do silhouettes to show shadows of the past, but also shadows of the knowledge that the Michi Saagiig women had that weren’t highlighted in any of Catharine Parr Traill’s writing, more so in Susanna Moodie’s written works.

Laura’s preparatory notes exemplified a “history of the present”—rethinking Catharine Parr Traill’s writings and letters as resources for present-day wellbeing: Two eyed seeing (Albert Marshall)—learning from one eye with the strengths of Indigenous knowledge and ways of knowing, and from the other eye with the strength of Western knowledge and ways of knowing—a gift of multiple perspectives; what I was trying to capture in this book, as well as the many strengths of the Michi Saagig people with respect to wellbeing practices…

Finally, Dorothy weighed in with her interpretations of Koren’s art work, highlighting the importance of a history of the present to create decolonizing art and to respond to the Calls to Action from the Truth and Reconciliation Commission:

Like Koren, I saw present-day Westove, the Lakefield home of Catharine Parr Traill in the 19th century and now Laura Elliott’s home in the 21st century, as a beacon to re-establish the early Indigenous-Settler friendships, and to acknowledge settler privilege and the suffering inflicted on Indigenous people through colonization. Settlers Catharine and her child and her Michi Saagig women friends occupying the two canoes flowing across the waters of Lake Katawanooska signals how Nature can heal the wounds of history.

I had another layer of interpretation because I had seen an earlier draft, in which there were no trees between the water and Westove. It occurred to me that this showed the clear-cutting of the old growth forests of Lakefield since Catharine Parr Traill’s time. I asked Koren if she could make the image more wilderness-y. The final image suggests to me that Settlers and Indigenous people alike need to make the effort to peer through deep truth forests in order to achieve reconciliation.

HARP’s catchphrase—A healthy community knows its history—is in accord with creating a history of the present.

Posted by Dorothy Lander: dorothy@tryhealingarts.ca The talented team at This is Marketing (https://www.thisismarketing.ca/) chose a unique colour palette to illuminate

L to R Clockwise: John Graham-Pole aged 2 on Mummy’s knee with sisters Elizabeth, Mary, and Jane, High Bickington, Devon,

Posted by Dorothy Lander Once a month, John Graham-Pole and I showcase the publications of HARP The People’s Press at

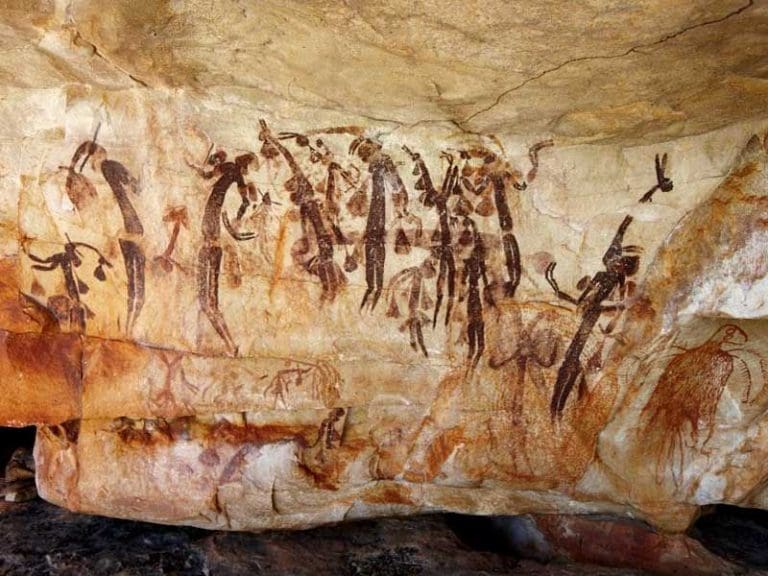

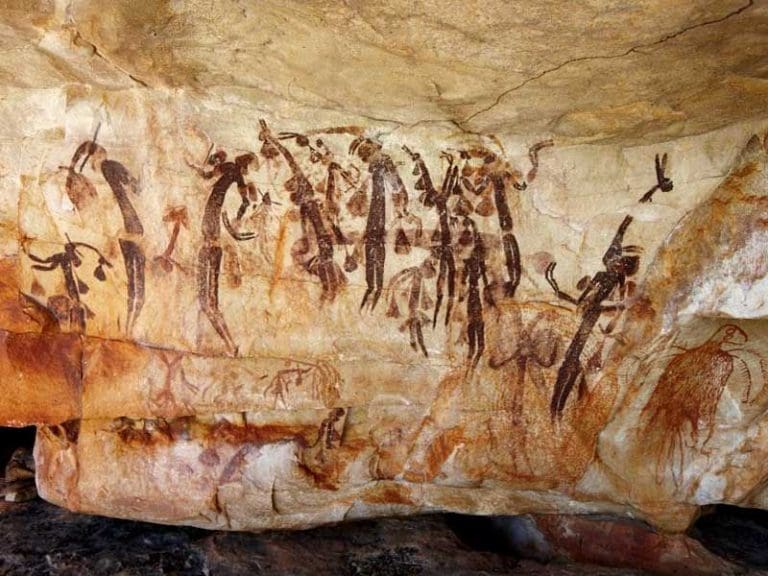

Aboriginal Rock Mural Kimberley Region, Western Australia Posted by John Graham-Pole I don’t have answers to any of these questions,

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |