Branding: Coordinating My Wardrobe to the HARP Colour Palette

Posted by Dorothy Lander: dorothy@tryhealingarts.ca The talented team at This is Marketing (https://www.thisismarketing.ca/) chose a unique colour palette to illuminate

By Dorothy Lander

“All my relations” is at first a reminder of who we are and of our relationship with both our family and our relatives. It also reminds us of the extended relationship we share with all human beings. But the relationships that Native people see go further, the web of kinship to animals, to the birds, to the fish, to the plants, to all the animate and inanimate forms that can be seen or imagined. More than that, “all my relations” is an encouragement for us to accept the responsibilities we have within the universal family by living our lives in a harmonious and moral manner (a common admonishment is to say of someone that they act as if they had no relations).

– Thomas King, All My Relations: An Anthology of Contemporary Native Fiction

(Thomas King, pseudonym Hartley GoodWeather, an American-born Canadian writer and photographer of Greek and Cherokee heritage, a Member of the Order of Canada and 2021 winner of the Stephen Leacock Award for Humour; he is regarded as one of the most influential Indigenous writers and scholars of his generation)

“A people without the knowledge of their past history, origin and culture is like a tree without roots.” – Marcus Garvey (a Jamaican-born Black nationalist and leader of the Pan-Africanism movement, which sought to unify and connect people of African descent worldwide)

“Understanding where we’ve been is the only way to know where we are going.” – Nina Rayburn Dec, Executive Director, Bridgehampton Museum, New York

“A healthy community knows its history” – Catchphrase for HARP Publishing: The People’s Press

As co-publishers of HARP Publishing The People’s Press (www.harppublishing.ca) Dorothy Lander and John Graham-Pole celebrate the power of the arts to heal every relationship on Mother Earth. Msit No’kmaq (All My Relations) embodies Indigenous Spirituality, which is vital to HARP’s mission and commitment to two related population health issues: truth and reconciliation with Indigenous Peoples and the existential biodiversity crisis. In this spirit, HARP donates 20% of sales to two organizations: The Circle of Abundance Indigenous Program, Coady International Institute, St. Francis Xavier University: https://coady.stfx.ca/circle-of-abundance; and David Suzuki Foundation (one nature): https://davidsuzuki.org

HARP is located in Mi’kma’ki (land of the Mi’kmaq), which includes the five Atlantic provinces and northern Maine, and was held in communal ownership, central to the gift economy. Every resource was considered a gift from the Creator. It was only with the arrival of colonists that the capitalist market economy became dominant, natural resources being treated as commodities to be bought and sold.

HARP is committed to the gift economy, even as it exists side by side with the market economy. Like all works of art, HARP publications are not commodities but gifts that combine several art forms. Lewis Hyde reminds us in The Gift that there is nothing in the labour of art that will automatically make it pay. The pejorative expression, “Indian giver,” tracks the history of colonization, which is predicated on private property and the market economy. Gifts given by Indigenous people to those first settlers were not deemed as free; they came with a responsibility: the gift must always move in a circle of reciprocity. In Braiding Sweetgrass Robin Wall Kimmerer calls this the covenant of reciprocity. Whatever we have been given must be given away again, or if kept something of similar value should move on in its stead (Hyde). David Suzuki’s relations with the world’s Indigenous People formed the foundation of his environmental activism. He insists Indigenous leadership and ways of knowing are imperative for the survival of human and other species: “Indigenous People all over the world refer to the earth as our Mother and say that we’re created out of the four sacred elements, earth, air, fire and water, that all living things are relatives. These are the perspectives, the attitudes, that are needed around the world to rediscover our place and respect for other creatures.”

Given that 80% of all species on Earth exist only in Indigenous territories, it is clear that Indigenous ways of looking after the land and water and all the species that live there, offers our best way forward for survival of all species.

After 44 years at the helm of CBC’s The Nature of Things, David Suzuki signed off on Friday April 7, 2023. In conversation with Piya Chattopadhyay on Sunday Magazine, CBC Radio, he declared TNOT to be the most important program on CBC because it tells science stories. He acknowledged that he was a storyteller, a science communicator, folding art into science. HARP has been making a case for not slipping the arts in sideways. I wanted to hear that narrative evidence is as critical as the scientific evidence in creating a change culture; Ellen Dissanayake’s research shows how art in all cultures, which she defines as “making special” often through ceremonies, promotes careful attention to abiding human concerns—even the very existence of the human species.

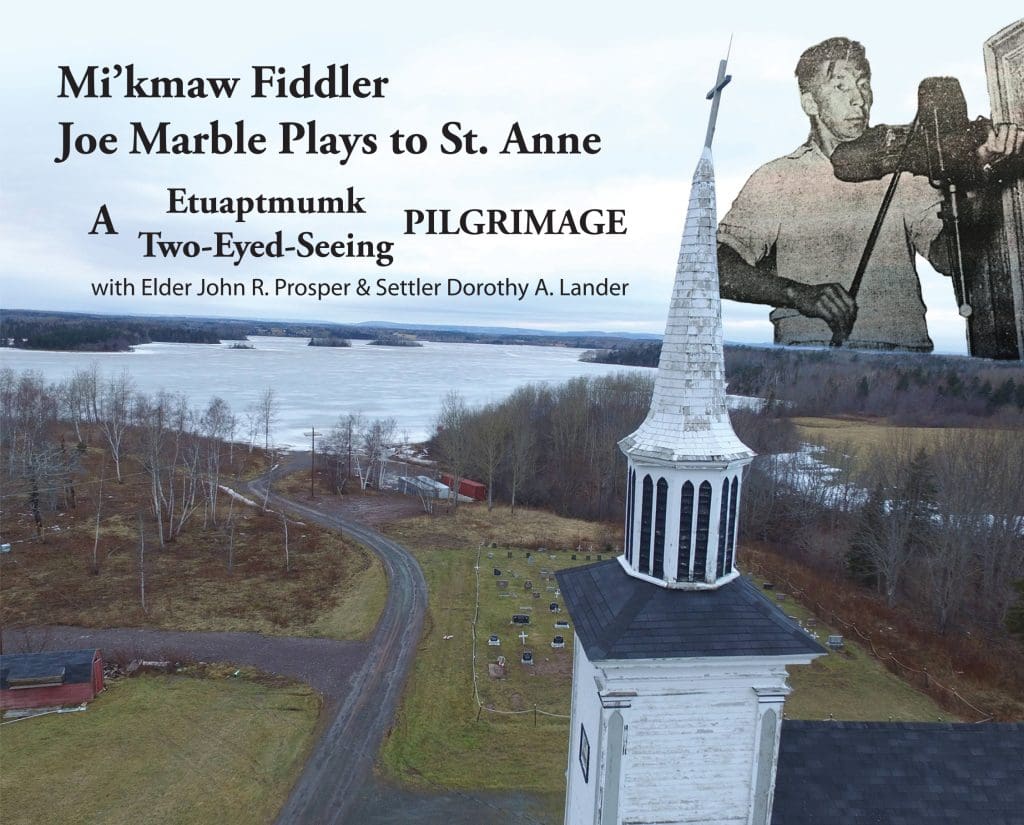

It is unrealistic to think we can turn back the pages of history and return all unceded land back to Indigenous Peoples. But David Suzuki challenges us to at least pay the rent—or in the language of the gift economy, we can reciprocate. The HARP publication that explicitly unfolds the circle of reciprocity is Mi’kmaw Fiddler Joe Marble Plays to St. Anne: A Etuaptmumk/Two-Eyed Seeing Pilgrimage by Elder John R. Prosper and Settler Dorothy A. Lander. https://stagingnest.tech/books/mikmaw-fiddler-joe-marble-plays-to-st-anne/ Eighty per cent (80%) of its sales, as well as all sales of used books in the HARP section of The Curious Cat bookstore on Main St. Antigonish go to the St. Anne Church Restoration Fund administered by Paqtnkek Mi’kmaw Nation. St. Anne is the patron saint of the Mi’kmaw Nation and the1867 heritage church and even older burial grounds on the coast of northern Nova Scotia constitute their spiritual home. But the market economy is still in play: HARP benefits from a charitable tax receipt.

Oxytocin – the Cuddle Hormone

Neuropeptide oxytocin, “the cuddle hormone,” gives us an intense feeling of belonging and connection, while decreasing our anxiety, lifting our mood and eliciting interpersonal bonding. In the HARP blog of January 2022, Dorothy wrote about the power of oxytocin, which is released by social touch such as breastfeeding, hugging, and making love. Oxytocin release underscores the principles of Msit No’kmaq—the gift economy—because the giving of this gift affirms a relationship between giver and receiver. “It is the cardinal difference between gift and the commodity exchange that a gift establishes a feeling-bond between two people” (Hyde).

Oxytocin is released not only during skin contact but when we engage with all creatures of the natural world—pets and houseplants, tarantulas and trees, rocks and ocean ripples. Emma Mitchell, author of The Wild Remedy, makes the case that we release oxytocin whenever we engage with the natural world or in artmaking with other people. Paul Zak, director of the Center for Neuroeconomics Studies at Claremont Graduate University in California, studies the social role of oxytocin, which is released during dancing, singing, meditation, and group marching, and even when we surmount a challenge—from the athletic to the interpersonal in family or workplace. Simple storytelling and listening releases oxytocin This Swedish study documents how storytelling increases oxytocin and positive emotions and decreases cortisol and pain in hospitalized children.

We humans are storytelling animals and our special gift is language, which—as Robin Wall Kimmerer tells us—comes with an obligation to move our words into the world as an offering to our Creator. Evolutionary anthropologist Ellen Dissanayake expands the gifts bestowed on humans to all acts of artmaking, all acts of “making special for someone,” thereby creating a relationship. So all our art is an act of reciprocity with the living land. We humans release oxytocin by way of “words to remember old stories, words to tell new ones, stories that bring science and spirit back together” (Kimmerer).

Oxytocin is rarely released in the market economy, which by contrast is largely responsible for increasing our carbon footprint—through corporate and government support for the fossil fuel industry, air travel and airports, and building a pipeline from the Alberta tar sands to the Pacific coast directly through the traditional territories of Indigenous Peoples. The market economy largely sees the arts as “frills” unless policymakers can see how they contribute to the bottom line.

HARP’s presentations, workshops, print and electronic publications, and social media postings have the capacity to forge a feeling-bond and release oxytocin: a win-win for people and planet. In the early 1990s, John Graham-Pole and his artist colleagues at the University of Florida asked the CEO of Shands Hospital to include their fledgling Arts-in-Medicine program in its budget by documenting “value-added” responses from patients and their families, staff and students. They came armed with charts showing 98% positive responses to questions like “Did you experience or witness benefits from making art?” An example of narrative evidence masquerading as quantitative, scientific evidence. The CEO, knowing the Arts-in-Medicine program was adding to the bottom line, at once committed $50,000 US to the hospital budget, and this budget has increased every year since.

Contrast this with for-profit health care and the fossil fuel industry, in which the marketplace dominates in international law and policy at all levels of government. The scientific genius of green technologies, energy transition initiatives, and recovery of native species can potentially unite the gift economy and market economy, yet is still overwhelmingly ignored. The more we offer the gift of art, the more oxytocin we release.

Msit No’kmaq

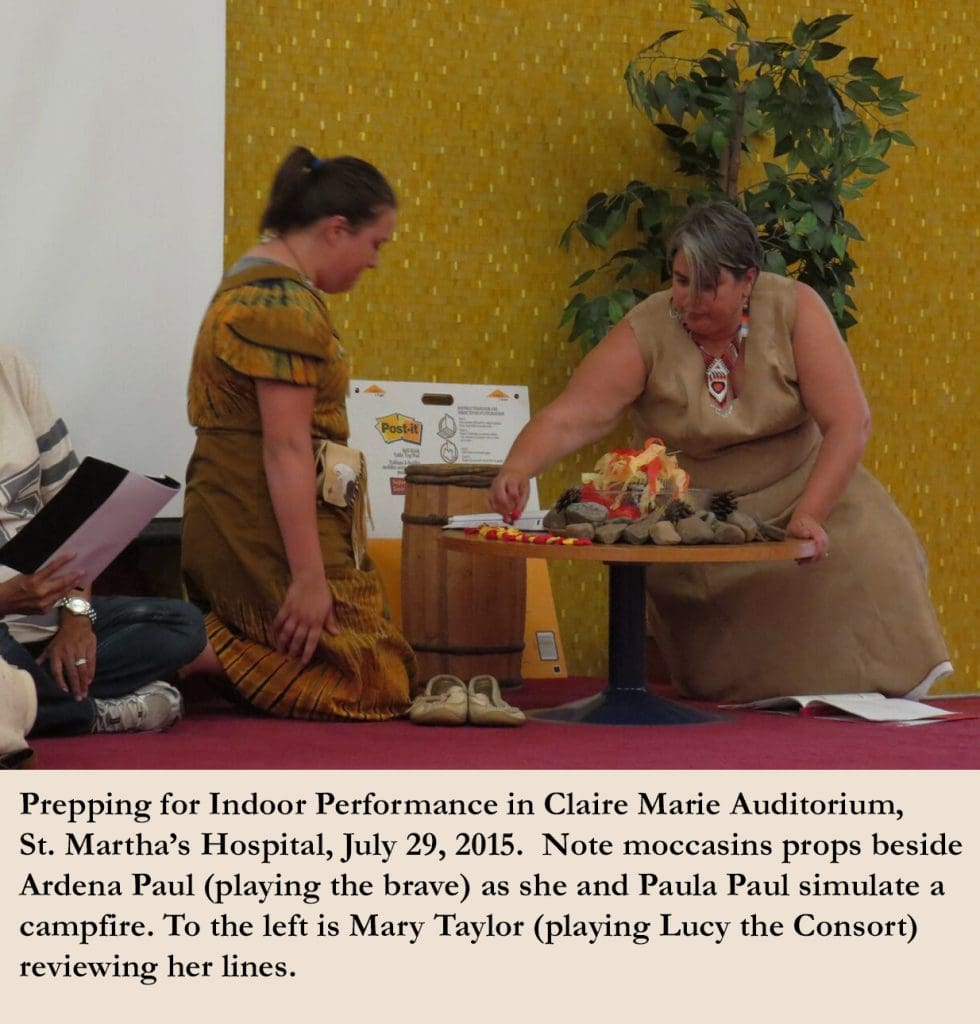

Dorothy knows the very moment she first heard Msit No’kmaq. In the summer of 2015, we were in rehearsals for the popular theatre/pilgrimage of 1784: (Un)Settling Antigonish, in which she had drafted a bare bones script on the founding of the first permanent European settlement of Antigonish at Town Point on Antigonish Harbour in 1784, relying on the 1935 biography by C. J. MacGillivray,The Times of Timothy Hierlihy. Shehad recruited performers from every nation that had a presence in those founding moments —Mi’kmaq, Acadian, African, Irish, Anglo-Celtic—and asked them to challenge and re-write the Eurocentric record.

Mary Taylor of Paqtnkek Mi’kmaw Nation played the part of Lucy, the Mi’kmaw consort to Captain Timothy Hierlihy (the Colonel’s son) and is buried with the Captain in the Church of England burial grounds at Town Point (see gravestone). It was Mary who re-wrote the script to incorporate the words into Lucy’s role, to signal the hospitality those first Antigonish settlers received from the Mi’kmaw People on whose lands they settled. This is just one of many passages that evolved collaboratively and incrementally with each rehearsal.

Lucy addressing Colonel Timothy Hierlihy:

I have to protest, Sir. First, the soldiers and their wives learned much more about foraging for food and game from my People than they did from the English women. And the uneasy relationship between my Mi’kmaw kin and the white man happened within my own household, our so-called Hospitable Lodge. I have a different interpretation on Mr. MacGillivray’s story of the “stalwart” and “fierce-looking” brave who ate the oyster dinner I had prepared for your son. It is true that I had prepared a dinner of oysters, bread and butter for the Captain while he was away hunting. This Mi’kmaw brave was well known to me and hospitality in our tribe means giving the guest the best of what you have to offer. Msit No’kmaq. Msit No’kmaq. This means “all our relations.” So of course, I invited him to partake of the oyster meal. I was NOT in “mortal terror,” as your biographer records, but when the Captain returned and became enraged that the meal was not waiting for him, yes, then I was alarmed. Especially when the Captain drew his sword on our guest — the precious sword that belonged to his Irish grandfather. I pleaded with him and eventually he stayed his hand. I hurried my kinsman out of the house and he disappeared into the woods.

The circle of reciprocity unfolds in the official biography and in our theatre/pilgrimage. The brave, realizing how he had innocently upset the peace in the household, returned a few days later and presented the Captain with a neatly made pair of moccasins. Mi’kmaw youth Ardena Paul played the part of the brave. Mary Lafford of Paqtnkek Mi’kmaw Nation created the old-style pair of moccasins, which we gifted to the Antigonish Heritage Museum, as a gift that moves across the centuries.

In the way of popular theatre, Mi’kmaw Elder Thomas Christmas rose from the audience and expanded on the words of Lucy, the Consort—Msit No’kmaq—noting that of course the Mi’kmaw helped the settlers survive when they landed at Antigonish Harbour, saying: “It doesn’t matter. If you’re human, you’re part of our family.” He shared his knowledge of the loss of biodiversity in Antigonish Harbour, which used to be the playground for porpoises. Until the settlers arrived, the Mi’kmaw harvested porpoises for oil, always according to the principle of “Take only what you need.” (Click on Youtube link)

Braiding Sweetgrass

A publishing house dedicated to the healing arts was not even a twinkle in our eyes in 2015 when we organized this pilgrimage to 1784: (Un)Settling Antigonish. In retrospect, we recognize that Msit No’kmaq, which unfolded in sharing circles throughout our pilgrimage, has guided us every step along the way, beginning with our decision to include braided sweetgrass at the top of our HARP logo.

After reading about the Covenant of Reciprocity in Robin Wall Kimmerer’s Braiding Sweetgrass, we have expanded the “All My Relations” symbolism of sweetgrass to acknowledge Indigenous stewardship of Mother Earth since time immemorial. Through the lens of braided sweetgrass, HARP’s catchphrase of “A healthy community knows its history” takes on the added imperative of reconnecting with seven generations of our ancestors to learn how to preserve and cherish Mother Earth for the seven generations to come.

The words of Anishinabe Elder Wally Chartrand on Facebook offer this guide:

Sweetgrass – a kindness medicine – has a sweet gentle aroma when we light it.

We use 21 strands of sweetgrass to make a braid. The first seven strands represent those seven generations behind us – our parents, grandparents, and so on back for seven generations. Who we are and what we are is because of them. They’ve brushed and made the trails we have been walking up until now. The old people tell us that it takes longer for us to heal today and the reason is because the old trails our ancestors used to use to find us have been destroyed. They’ve build dams which have destroyed the old trails. They’ve build towns and cities where the old trails used to be. So now our ancestors are having a harder time trying to find us to help us heal.

The next seven strands represent the seven sacred teachings: love, respect, honesty, courage, wisdom, truth, and humility. The old people tell us how simple, powerful and beautiful the teachings are.

The last seven strands are for the seven generations in front of us: our children, our grandchildren, and those children yet to be born. Why are they important? Everything we do to Mother Earth will one day affect them. Right now the earth gives us everything and anything we can possibly want to have the life we have, but if we don’t look after her, what’s going to be left when it’s their turn?

We put those three braids together, and they represent yesterday, today and tomorrow…mind, body and spirit…man, woman and child…man, woman and Creator.

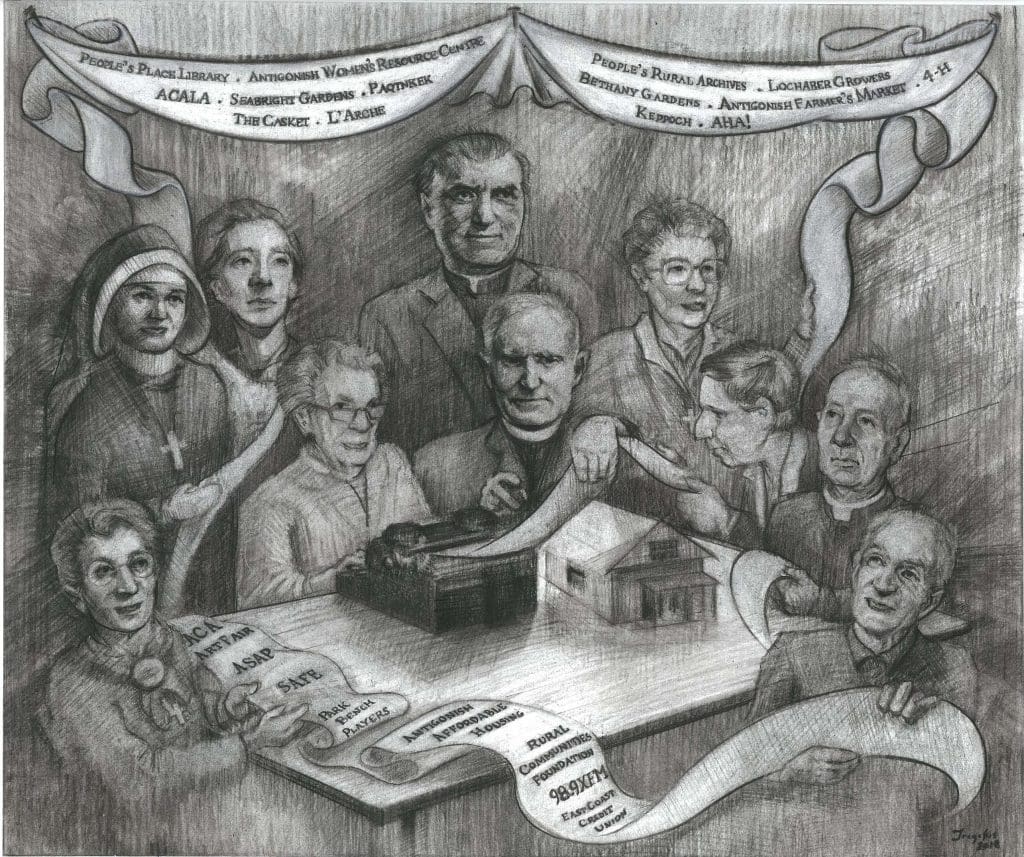

Gifts that Move

The oral tradition of sharing circles has been part of Indigenous cultures since humans first evolved as storytelling animals. Story sharing stands out as the oxytocin-releasing constant that creates the social bond necessary for navigating everyday challenging social situations. Shared stories and the braiding of those stories shaped HARP’s first publication in December 2018, The People’s Photo Album: A Pictorial Genealogy. Echoing sharing circles, the descendants of the early Antigonish Movement from northern Nova Scotia, and those living the legacy of this social movement internationally through the Coady International Institute, “took turns” in sharing their photos, artwork, newspaper clippings, and stories, which they pulled out of letters, scrapbooks, and family albums of their ancestors and off their own smartphones and social media platforms.They were able to express their feelings, thoughts, and experiences in a non-judgmental, safe space and to engage each other’s active listening. The textual sections of The People’s Photo Album, including the handwritten letters featured on many of the pages, tell the “small stories” of the Antigonish Movement—the “kitchen table” stories—which serve to reinforce the published “great men” stories. The back cover artwork by Adam Tragakis entitled Kitchen Meeting features the known names of the Antigonish Movement—Fr. Moses Coady and Fr. Jimmy Tompkins—but also the women founders of the Movement like the Sisters of St. Martha, and the women librarians and cooperative housing organizers, who are not household names.

The gift that moves was the operating principle for The People’s Photo Album. The Phee family represented here by Barb Phee, Johnny Phee Junior, and Sylvia Phee, who were major contributors to the page on the Martin Street Housing Cooperative, met with Dorothy at the Atlantic Superstore for a photo op and ceremonial opening of the Album to the page where they are represented. This is unlike any other exchange at the Superstore, where typically the relationship ends at the check-out line.

There is no end timeline for the gift that moves, or for the relationship that accompanies it. A year after the launch in December 2018, Carla, another Phee sibling, living in Alberta, ordered the personal pages package, the 6 pages that featured her family plus the Kitchen Meeting sketch. She wrote, “I grew up on Martin Street and I thought it would be a special gift to show my kids about the history of The Martin Street Housing Cooperative.” Then in late 2021, Rose Murphy, reporter and associate producer for CBC Radio Halifax, asked for copies of the pages related to The Martin Street Cooperative for a story to air on Information Morning on Jan. 3, 2022. In 2023, the full story complete with interviews with the Phee family will be aired on Atlantic Voices, the Sunday morning show on CBC Radio Halifax. Also in 2023, HARP will have the debut showing of “The Unsung Heroes of the Antigonish Movement,” created by Antigonish filmmaker Denise Davies and featuring many of the unsung heroes from The People’s Photo Album. The Coady Institute funded this documentary film, which they will use as an educational resource. This example responds to the call, which Robin Wall Kimmerer describes as going beyond “cultures of gratitude, to once again become cultures of reciprocity.”

The launch of The People’s Photo Album on Dec. 6, 2018, at the East Coast Credit Union Social Enterprise Centre was the defining moment for oxytocin release and a culture of reciprocity. The Van de Weil family, who are well-represented in the Album, composed the lyrics and musical accompaniment for Let’s Go Make a Difference in the World, which the diverse community sang together in solidarity. (Tune in on the YouTube link).

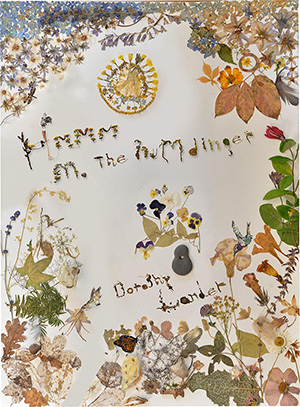

Dorothy’s botanical children’s book, Hmmm: M the Humdinger, tells the story of M, a child of nature who communicates entirely by humming. It must have released a lot of oxytocin as it was created through sharing stories and crafting with other people. It is available in print and as an online Flipbook with a humming soundtrack. Think of the oxytocin being released by and for readers: the story itself invites intergenerational readers to hum along together every time Hmmm appears in the book. Not much oxytocin gets released in academic publishing. It is worth considering that reading stories aloud together and humming together offers a delightful way of lowering our carbon footprint. https://stagingnest.tech/books/hmmm/

Unlike “blind reviews” that academic books and research articles call for in the interests of “objectivity,” authors in the popular press ask for testimonials (blurbs) in which the reviewers do not hide their identity, often adding to their name credentials, book titles, and awards. The (loving) testimonials for Hmmm came from All My Relations—three generations of Dorothy’s family, including her grand nieces and nephews. Many testimonials came in the form of stories like Dorothy’s grandnephew Tannen remembering his times at the Valley of the Big Stone with his Grandpa Lander, which features in the story of M meeting the Wise Woman. Experts on humming like evolutionary musicologist Joseph Jordania, plant whisperer Rachel Corby and evolutionary anthropologist Ellen Dissanayake also gave testimonials. Ellen’s s cat Kiisa weighed in on the online humming parts, affirming Msit No’kmaq.

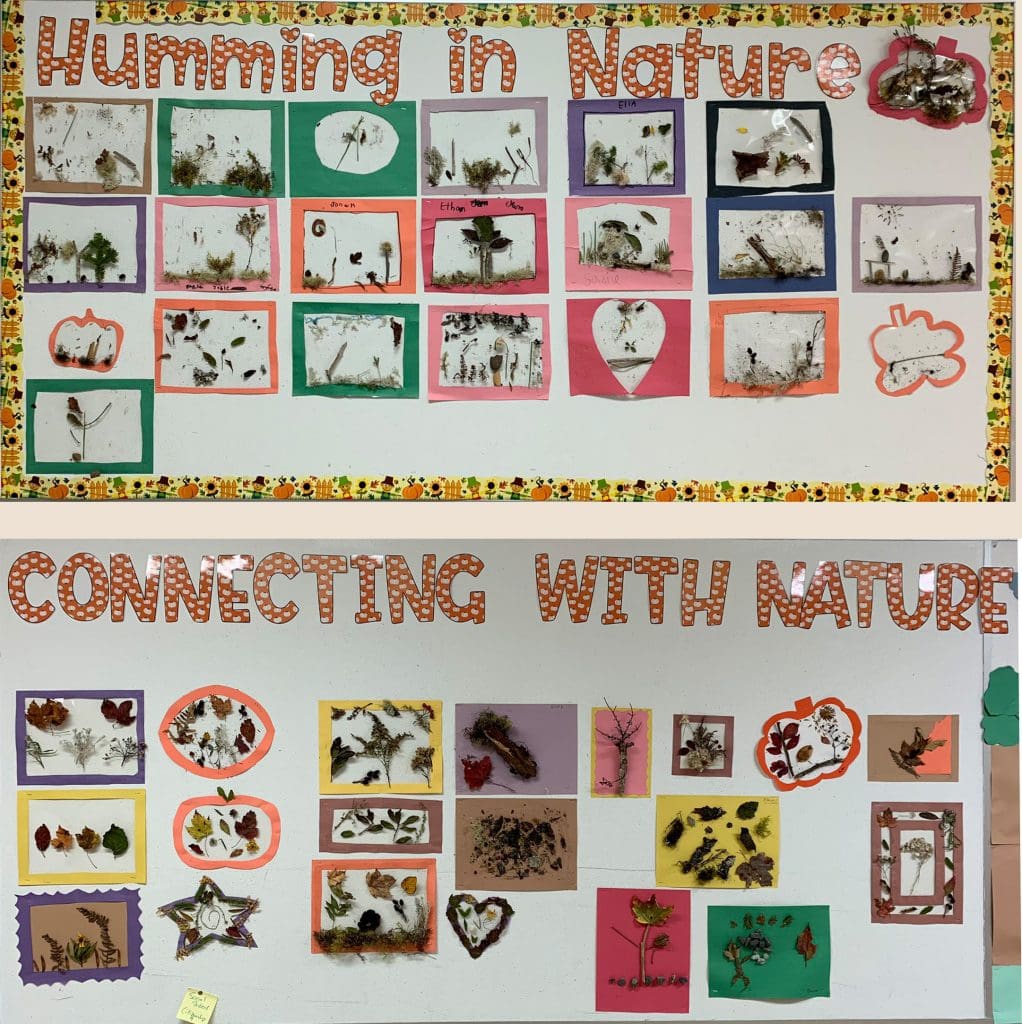

Hmmm, a gift that moves, enacted the covenant of reciprocity when Lynn Casey, Principal of Fanning Education Centre/ Canso Academy in Guysborough County, Nova Scotia, introduced this book to students in several grades. The students offered up their gifts on behalf of the earth in their drawings and botanical pressings. Plans are underway for a four-season Knowledge Path in this historic town, in which humming in nature will feature.

Virtual Oxytocin Release

The physical isolation that the pandemic imposed on us in 2020 inevitably reduced the release of oxytocin that comes with social touch. Even as air travel declined and the air in the “big smog” cities of London, Toronto, and Cairo cleared, our mental health deteriorated. People who began working from home continue to do so even as the pandemic restrictions have lifted; and many have developed “skin hunger,” leading to a surge in demand for mental health services. Meanwhile, Zoom meetings have escalated. Physician Jena Lee associates “zoom fatigue” with the challenges to oxytocin release, the downside of videoconferencing. Personal eye contact improves connection, and during zoom conferences of more than three, it is impossible to distinguish mutual gaze between any two people. Moreover, the unconscious and nonverbal communication that we process through touch, joint attention, facial expressions, and body posture are hard to capture on Zoom. The inevitable technogical glitches and audio delays — “Are you there?” “Can you hear me? —can engender distrust. We believe that our virtual book launches on Zoom and streamed on Facebook mitigate some of these challenges to oxytocin release.

We launched Singing to the Darkness, a visual inquiry by HARP’s first Indigenous author Patricia June Vickers over four Thursdays in June 2020. On each occasion, Patricia was interacting with one or two people at a time, which then allowed guests to witness the strong connections between Patricia and her guests, who included her editor Leslie Eliel, Resiliency scholar Dr. Martin Brokenleg, and compassionate inquiry practitioner and trauma and addiction scholar Dr. Gabor Maté. On each occasion, Indigenous Elders led off with a ceremony—a prayer, the beat of drums. https://stagingnest.tech/singing-to-the-darkness-join-us-for-the-feast-hall-book-launch/

Also in 2020, Kyla Heyming, currently Poet Laureate of Sudbury, organized the launch of her poetry collection For Those I Have Loved streamed on Facebook and in-person in Sudbury. As we “attended” the Facebook launch, we witnessed the loving kindness of Kyla’s friends and relations as they worked through the initial audio glitches. Quite the opposite of distrust, we had a vicarious experience of oxytocin release as Kyla read from her poems.

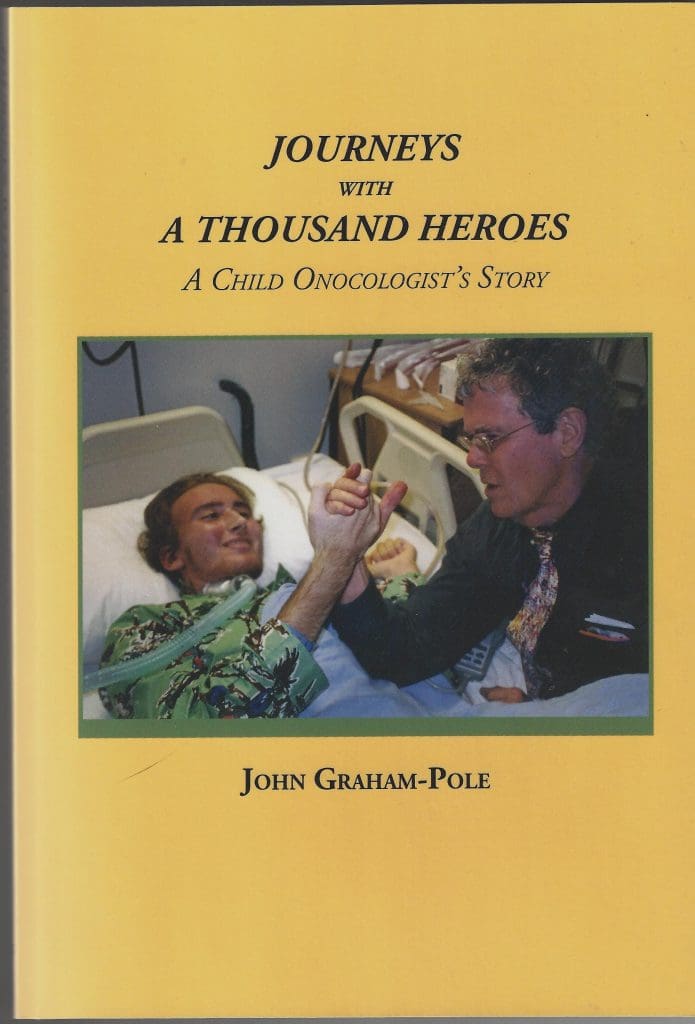

John‘s young adult novels and memoirs are testimony to works of art as gifts that move. John reconnected with the families of children he cared for who died and also with children now grown up with families are their own. John features his patient Jarrad on the front cover of Journey with a Thousand Heroes and tells how the gift of play in his treatment practice 20 years earlier mattered and moved. Jarrad’s Mom Colleen Kogos offered a testimonial (blurb) for John’s medical memoir, which was in turn a gift to John. “In a sky of shining stars Dr. Graham-Pole was our North Star out of darkness.” John also features Antigonish artists in his trilogy of young adult fiction, his memoir Healing by Intent, and Illness and the Art of Creative Self-Expression.

Truth and Reconciliation

HARP’s acronym H-ealing A-rts R-econciling P-eoples signals our obligation to respond to the Calls to Action from the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, to apply the arts toward healing the wounds in Indigenous-Settler relations. The popular theatre/pilgrimage event 1784: (Un)Settling Antigonish, followed by the eponymous DVD featuring interviews with cast and crew and audience members, has pulled HARP directly into the circle of reciprocity today. In a submission to the Aquaculture Review Board, we challenge the omission of Indigenous voices and treaty fishing rights in the hearing of the application by a Town Point family for a large-scale commercial oyster fishery in Antigonish Harbour, the very site of our outdoor performances in 2015. We copied local, provincial and federal government officials, including the Minister and Parliamentary Secretary for the Department of Oceans and Fisheries Canada, which in March 2023 announced a commercial oyster fishery led by Paqtnkek Mi’kmaw Nation in nearby Pomquet Harbour. The Mi’kmaw right to fish for food, social, and ceremonial needs, and for a moderate livelihood, is recognized by the Supreme Court of Canada and protected by the Constitution.

Our submission to the Aquaculture Review Board referencing HARP’s documentary film 1784: (Un)settling Antigonish and the blog on the HARP website, Travels with a Low Carbon Couple, soon to become a HARP title in print and electronic versions, are deeply influenced by our relationships with Indigenous Peoples. https://stagingnest.tech/books/1784-unsettling-antigonish-film/ Because colonization is deeply connected to the loss of biodiversity and our endangered human species, colonization is also a public health issue. Tynette Deveaux from Sierra Club Canada’s Beyond Coal campaign takes this up in Episode 6 of the Ecology Action Centre’s video series, “Voices on the Climate Plan.” She calls the Nova Scotia Climate Plan of 2022 “a distraction,” and urges us to put our efforts toward changing current systems of capitalism and colonialism.

Several of our multi-media publications are “gifts that move:” they take up truth and reconciliation themes and feature the words and art of both settlers and Indigenous people.

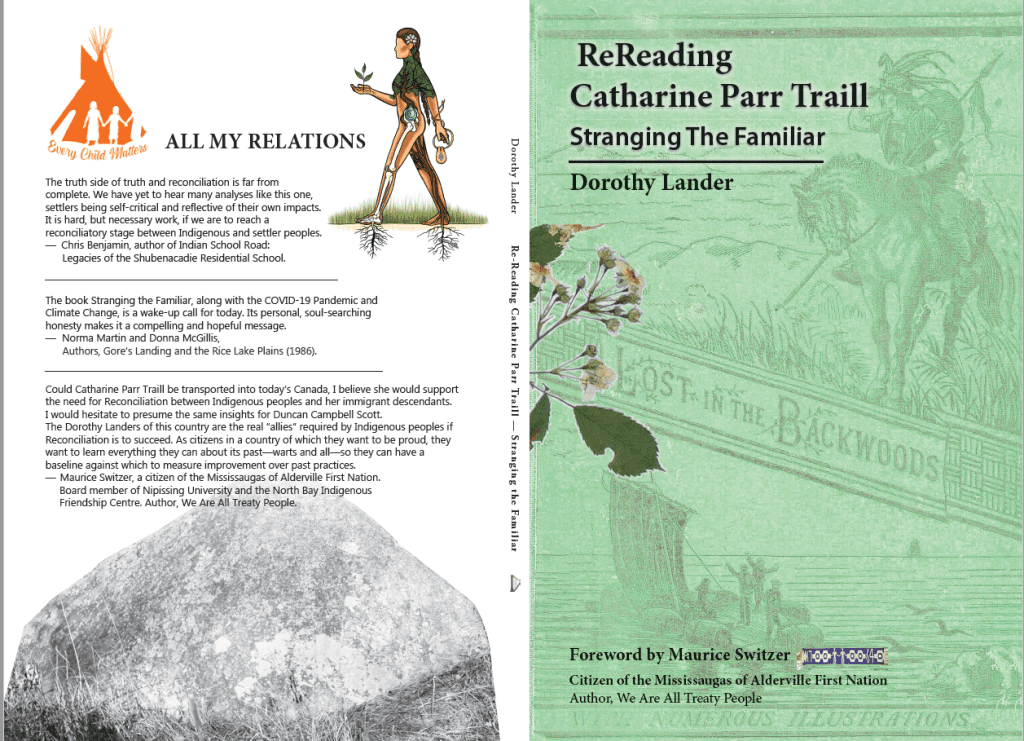

On September 30, 2022, we launched ReReading Catharine Parr Traill: Stranging the Familiar by Dorothy Lander, Foreword by Maurice Switzer and Artwork by Koren Smoke, both citizens of the Mississaugas Alderville First Nation, as a Truth and Reconciliation event. https://stagingnest.tech/books/rereadingcpt/ We chose St. George’s Anglican Chapel in Gore’s Landing overlooking Rice Lake for two reasons. The Traill family attended this church and Catharine’s grandson, Henry Strickland Atwood, aged 3 years old is buried in the churchyard.

We enacted All My Relations and the gift economy in several ways. Many Mississaugas as well as Dorothy’s relatives and childhood friends were in attendance, even her 96-year-old Girl Guide Leader, Norma Martin. Dorothy and her childhood bestie Brenda Jackson Manley chose 19th-century Nature hymns like All Things Bright and Beautiful and handed out song sheets. Brenda played the organ and we Settlers and Mississaugas of the Rice Lake Plains all sang together. Dorothy’s cousin Trevor Joice sound engineer for community radio Northumberland 897 recorded the event, which was aired on Oct. 5, 2022.

Mandy Martin, whose father Rev. Dr. Norman Martin was the rector at St. George’s for over 30 years, hosted the event. At the end of the presentation, Mandy led a talking circle using a first edition of Lost in the Backwoods as a talking stick; settlers and citizens of Alderville First Nation shared their stories of Indigenous-settler relations, both positive and negative. With our invitations to the event, we asked that attendees bring white and orange flowers to lay at Baby Henry’s grave as a gesture of reconciliation – Every Child Matters. Artist Koren Smoke, Skye Anderson and her children from Alderville led the Every Child Matters procession to the gravesite.

We view the world and all that it is in it as having spirit, that all life is equal to our own and must be treated with respect. We are inspired by the Mi’kmaw beliefs that the relationships between the living and the non-living tell a story that can guide all peoples to survival of our own and other species. We approach animals and plants as our relatives and try to take from them no more than we need.

“We are all Treaty People.”

Tags: climate change healing arts Health Equity Indigenous knowledge Nature Writing publishing Social Inclusion

Posted by Dorothy Lander: dorothy@tryhealingarts.ca The talented team at This is Marketing (https://www.thisismarketing.ca/) chose a unique colour palette to illuminate

L to R Clockwise: John Graham-Pole aged 2 on Mummy’s knee with sisters Elizabeth, Mary, and Jane, High Bickington, Devon,

Posted by Dorothy Lander Once a month, John Graham-Pole and I showcase the publications of HARP The People’s Press at

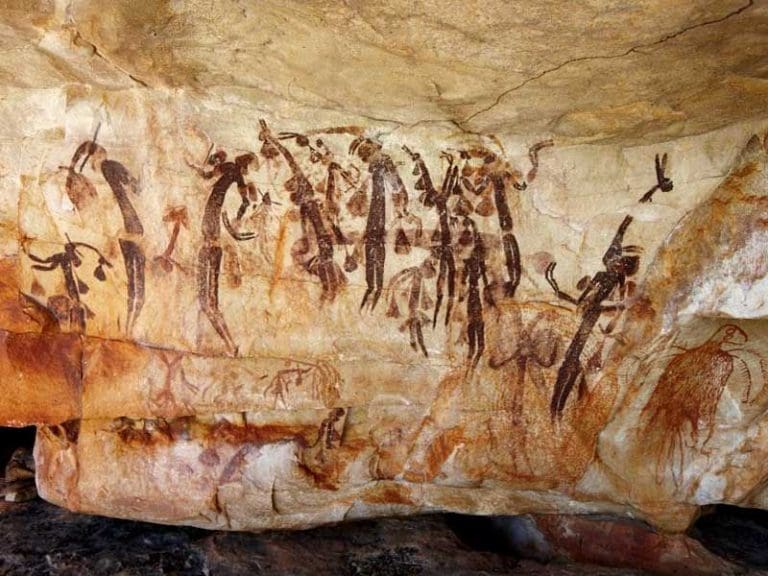

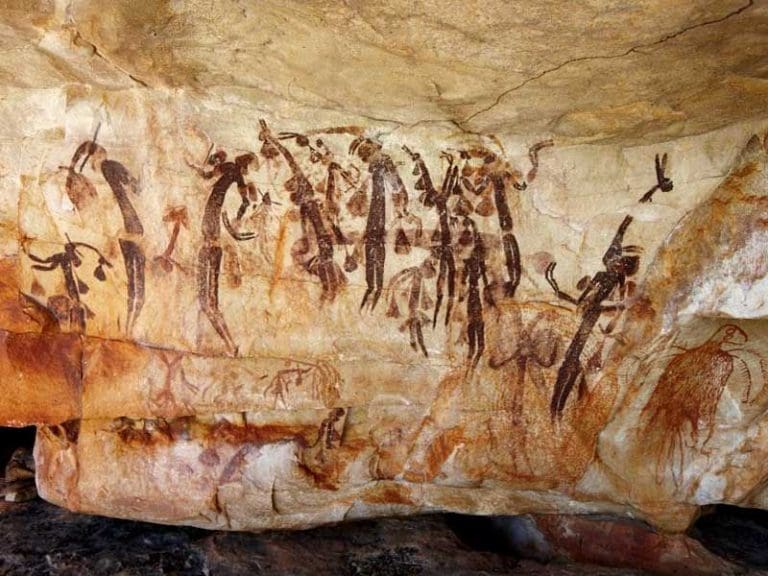

Aboriginal Rock Mural Kimberley Region, Western Australia Posted by John Graham-Pole I don’t have answers to any of these questions,

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |