Branding: Coordinating My Wardrobe to the HARP Colour Palette

Posted by Dorothy Lander: dorothy@tryhealingarts.ca The talented team at This is Marketing (https://www.thisismarketing.ca/) chose a unique colour palette to illuminate

Poking out of the top of my 2022 Christmas stocking was the book Peace by Chocolate: The Hadhad Family’s Remarkable Journey from Syria to Canada by change-maker/author Jon Tattrie. Also two dark chocolate bars—70% cocoa—from the Hadhad’s newly opened store on Main Street, Antigonish.

Shortly after midnight on the first day of 2023, having blurted out “Rabbits” as my first utterance following the English good luck tradition of my husband/co-publisher John Graham-Pole, I was wide awake. I decided to read just a few pages of Peace by Chocolate to help me sleep. I was instantly drawn in. By the time dawn was breaking In Nova Scotia on New Year’s Day, I had read it cover to cover.

HARP The People’s Press is the healing arts publishing house that John and I established in 2018 (www.harppublishing.ca) and the books we read, write and publish are dedicated to the arts for health equity. I wondered if Peace, which the World Health Organization names as a social determinant of health (SDH), would be the unifying theme. But no. Enthralled as I was with each turn of the page, I soon knew that the Hadhad family’s journey from Syria to Canada was an exemplary model of the Cooperative Arts—an equally compelling SDH now identified by WHO as foundational for health equity.

I was moved to write this blog entry to our website to show how Peace by Chocolate, the book, constitutes a healing arts primer for understanding the assets and barriers to health and wellbeing in the experience of new immigrant Canadians as well as their sponsors and allies. American psychologist Rollo May uses a chocolate-y kind of metaphor to pose the question: “What if imagination and art are not frosting at all but the fountainhead of human experience?”

The courage to create even in the direst of circumstances is the unifying story in this book. Isam, the artisan chocolatier and father of the family , described for Jon Tattrie his early fascination with the intimate, edible art of chocolate-making. “We are born with our raw ingredients…and poured into a mould called adulthood. But the chocolate is not the mould, and neither are people. You can always melt chocolate and make it into a new shape” (p. 19).

Jon Tattrie’s approach throughout echoes a HARP catchphrase—A healthy community knows its history: the history of chocolate in the Prologue; the Hadhad family history in Damascus; and the ancient and more recent war-dominated political history of Syria in Chapters One and Two; the post-2010 Syrian diaspora to Lebanon, Greece, Germany, and North America; and the UN and Canadian embassy connections to the Hadhad family in Chapters Three and Four; and in Chapter Five the roots of the welcoming community of Antigonish, both through its Indigenous origins and its social justice history embodied in the Antigonish Movement.

HARP’s first publication, The People’s Photo Album: A Pictorial Genealogy of the Antigonish Movement, launched in December 2018, documents the legacy of the early Antigonish Movement, most often associated with the Sisters of St. Martha, Fr. Moses Coady and Fr. Jimmy Tompkins, through 21st century social-justice organizations and movements, including SAFE (Syria-Antigonish-Families-Embrace) and the International Pot Luck Group. Jon Tattrie takes this up in Chapters Six, Seven, and Eight, reinforcing the message of Adam Tragakis’s Kitchen Meeting gracing the back cover of The People’s Photo Album. Here Zita Cameron is positioned at the typewriter that produced Masters of Their Own Destiny, Dr. Coady’s 1939 classic, that takes up the peace and cooperation mantra. ”Man was not made for bestial fighting.” Rather, “we are born to make art.”

In Adam Tragakis’s sketch, the early champions of cooperative housing, coop grocery stores, community gardens, credit unions, and adult education study circles are represented as a kitchen meeting. Their banners identify the present-day organizations that embody the spirit of the Antigonish Movement. Included on the long list that Adam imagined these pioneers coming up with are SAFE, the People’s Place Library, ACALA, the local newspaper The Casket, and The Antigonish Farmer’s Market. It is no coincidence that these all feature in the Hadhad family’s journey.

It was several months after the Hadhad family of refugees arrived in Antigonish, and long before Peace by Chocolate was an internationally known brand, that Isam summoned the courage to once more create chocolate products—hearts and maple leafs and bars—using the Hadhad kitchen as his factory. With a lot of help from his family and newfound friends like Frank Gallant, his very first Canadian-made chocolates found their way to the winter farmer’s market in Antigonish. They sold out before noon on their first day at the market (p. 132). And continued to do so every Saturday morning.

Eating together is the great leveler featured at the International Pot Luck dinners at St. James United Church. Here Dr. Robert Sers is sitting with the Hadhad family. Robert Sers and his wife Moira hosted Tareq when he arrived on his own in snow-bound Antigonish in December 2015 in advance of other members of the Hadhad family (p. 97). For that first dinner party with Tareq and SAFE volunteers in the Sers home, Moira had cooked a Middle Eastern meal of halal chicken. A healing welcome: “The smells of spices and meat reminded Tareq of family feasts at home (p. 98).” Tareq did not hesitate to get in on the movement by drumming at the Pot Luck dinners with participants at the Coady International Institute at St. Francis Xavier University.

In 2014, we organized our heritage photos for a community health project we named Imagine Antigonish with the Cooperative Arts as the underpinning for all the other Social Determinants of Health (www.imagineantigonish.ca). The peace-making culinary arts, specifically Chocolate Arts, reinforce the other health-affirming factors in the Hadhad family’s story.

Social Support Networks have long been named as vital to our health and wellbeing. The social support networks in Antigonish hatched SAFE after Lucille Harper gathered fourteen people to talk about the possibilities of the community supporting a refugee family. Heather Mayhew, a volunteer with Antigonish Poverty Reduction Coalition, and her husband Frank Gallant offered a highly creative plan. They had bought and repaired a yellow two-storey house close to the centre of town and just down the hill from St. Martha’s Hospital. They were eager for Antigonish’s first Syrian family to move in. The house stands as a symbol of the intertwining of the cooperative arts for health equity, which embrace Housing and Infrastructure, Social Support Networks, and Cultural Sensitivity. The allies in Antigonish installed fitted blinds in each window, recognizing that “for Muslims, a home has to be a fully private place (p. 87).”

The arts explicitly figure in Batoul’s journey to wellbeing. As the teenager in the family, she was distraught at leaving her friends and fleeing to Lebanon, then after making new friends there, once again being displaced to Canada. She hated the cold. Carly, her first friend at high school in Antigonish, recognized Batoul’s eye for photography. Something about the winter beach and “its austere majesty appealed to her and she captured the way the sun played on the sand and water. Everything filled her with awe. She processed her new home photo by photo (p. 121).” She sent the photos to her sister Alaa and the children Omar and Sana who were still in Lebanon. She was playing the flute at high school “and finding the universal language of music filled her with joy (p. 137).”

Literacy is a recognized social determinant of health. ACALA (Antigonish County Adult Literacy Association) meets in the People’s Place Library. Here Shahnaz, the mother of the Hadhad family, with Rabiaa, the mother of another Syrian family that arrived soon after the Hadhads, are learning English in the ACALA meeting room.

The public face for Peace by Chocolate belongs decisively to Tareq Hadhad, the oldest son of Isam and Shahnaz, and now the named CEO. Tareq has a natural alignment with the healing arts. He had nearly completed his medical studies at Damascus University and when the family fled to Lebanon in 2015, he volunteered for the United Nations mobile medical clinic, developing programs for refugees that spanned protection against diseases, hygienic practices, and legal rights. He had ambitions to become a physician in Canada. The stories that Jon Tattrie highlights in the book reveal an entire family of healing arts practitioners.

The ideas in Malcolm Gladwell’s (2000) The Tipping Point offer a framework for this healing arts case study. Gladwell’s Connectors, Mavens, and Salespersons stand out in the Hadhad family and among their community allies, with specific instances of their roles in doing “little things that make a big difference,” so critical for a product or a movement going viral. A “little thing,” a life-affirming thing, greeted Tareq when he landed in Toronto. David Johnston, the Governor General of Canada, welcomed him and called the newcomers “new Canadians—from the moment they landed (p. 92).”

Isam’s prodigious knowledge of chocolate-making places him as Maven: “He gained control over the mysterious process (p. 19).”

Shahnaz is the Chief Executive Connector, dedicated to keeping her family intact. Drawing on her wide support network and the Lebanese Underground Railway, she helped find the apartment in Saida, a port town in Lebanon. It was Shahnaz who was calling her son Tareq every hour while he was flying alone to Canada in December 2015. Once settled in Canada, she was in daily contact with her daughters, texting and speaking to them via WhatsApp phone calls or video chats: Kenana, their eldest, still in Damascus with her husband and children, Walaa in Saudi Arabia with her husband, and Alaa who was still in Lebanon taking care of her two young children and hoping to find out what had happened to her husband Mamouth and his brothers who had disappeared in Syria a year earlier. Access to social media intersects with social support networks to support health equity. Shahnaz prophetically announced to Isam, who despaired that he could ever recover his ruined dreams, “We can rebuild—and quicker than before, better than before. … Maybe you can meet Justin Trudeau” (p. 124).

Tareq is the Salesperson par excellence who “infects” others with emotions and through his spontaneous humour; Indeed, Tareq’s emotions were contagious. A positive epidemic! Neil Stephen and his wife Kirsten set up their own marketing company in Halifax after finishing high school and university in Antigonish. They offered their marketing skills pro bono to help the Hadhads develop their brand. A ‘little thing” on the way to a tipping point was naming the brand. Tareq knew he wanted to connect Syrian chocolate to peace. In a flash of inspiration, Neil scribbled the three-word phrase “Peace by Chocolate.” Tareq smiled and pronounced it “perfect.” By the Spring of 2019 Tareq had delivered more than 450 speeches around the world.

Income Security has long been recognized as a contributor to health and well-being. The Sobeys grocery chain became the major distributor for Peace by Chocolate in its stores across Canada, and it soon became clear that the Hadhad family needed a larger factory than the small shed attached to their little home that Heather and Frank had prepared for them. When Sobey’s provided the building for a big factory on the outskirts of Antigonish, Peace by Chocolate was poised to become one of the town’s most important private employers—thirty at the time Jon Tattrie was writing the book, and many more now.

By the time of the grand opening of the Peace by Chocolate factory on Cloverville Road on Sept. 6, 2018, Tareq’s identity as an entrepreneur had begun to overtake his identity as an aspiring physician. In his first year in Antigonish, Tareq had collaborated with John Graham-Pole, known internationally as a pioneer in the arts-in-medicine movement, participating in Arts Health Antigonish! (AHA!) projects. AHA! is yet another organization on the list coming out of Zita Cameron’s typewriter in the Kitchen Meeting. I have dubbed the picture of John and Tareq at the grand opening “The Dance of the Docs,” which is included on the SAFE pages in The People’s Photo Album. John retired to Antigonish in 2007 after 40 years of doctoring in the UK and the USA. He likes to say that he “practices without a license” in Canada. Both Tareq and John are CFAs (Come from Away), who proudly became Canadian citizens and cherish their Canadian passports.

So what of Tareq’s dreams? The other treasures in my Christmas stocking—the Peace by Chocolate bars—signal a “little thing” that confirms that Tareq too has a healing arts practice in Canada.

The high sodium content in processed food is a public health issue. As seniors, John and I are serious about reducing our salt intake; grocery shopping includes a careful scan of the ingredients, rejecting products with high sodium in favour of products that use potassium. The slogan “One Peace Won’t Hurt” takes on added meaning: 250 mg of potassium and 0 mg of Sodium in four pieces of chocolate. Both entrepreneur and healing arts practitioner, Tareq’s medical training inspires his courage to create.

Posted by Dorothy Lander: dorothy@tryhealingarts.ca The talented team at This is Marketing (https://www.thisismarketing.ca/) chose a unique colour palette to illuminate

L to R Clockwise: John Graham-Pole aged 2 on Mummy’s knee with sisters Elizabeth, Mary, and Jane, High Bickington, Devon,

Posted by Dorothy Lander Once a month, John Graham-Pole and I showcase the publications of HARP The People’s Press at

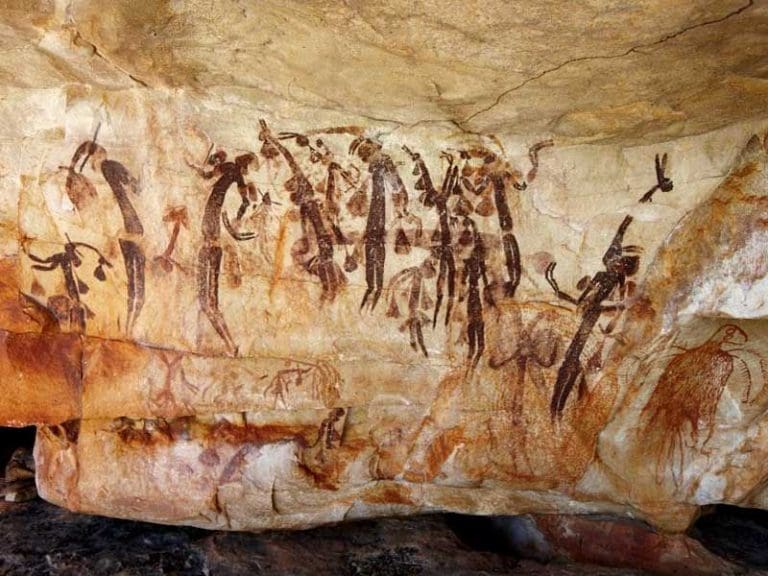

Aboriginal Rock Mural Kimberley Region, Western Australia Posted by John Graham-Pole I don’t have answers to any of these questions,

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |